January 24, 2022

The Bedouin, the State, and Statelessness: Mobility, Identity and Resilience

Until recent times, most Bedouin were pastoral nomads; movement was an essential part of their lives and livelihoods. Their experience is a chance for us to reflect on how historically mobile peoples enter into our conversations about statelessness today. Where do they fit in a nation-state order, with its territorial borders and assumed nationalities? How far have they been seen to challenge this order – or, indeed, the state itself? As we shall see, some Bedouin have faced discrimination and social exclusion, their credentials as 'citizens' cast into doubt even if they were not taken away. Many have been alienated from lands they had long used for grazing, when the state claimed great swathes of desert and steppe for itself. Others, unable to document their long-term settlement in a given national territory, have been denied nationality altogether. Still others, however, played a prominent part in the creation and development of the very same nation states. In this way, the history of Bedouin communities in the Middle East – communities whose self-identification reaches across and through national borders, and whose mobility has so often defied state authority and state definition – is a history of statelessness in a different sense: not necessarily one of lack of nationality, but sometimes representing a challenge to it, and sometimes in ambivalent co-existence with it.

In this way, the history of Bedouin communities in the Middle East is a history of statelessness in a different sense: not necessarily one of lack of nationality, but sometimes representing a challenge to it, and sometimes in ambivalent co-existence with it.

The first step in unravelling this complex relationship lies in recognising the immense changes in Bedouin lands, lives, and fortunes in the hundred years since the First World War. In 1918, the vast and multi-ethnic Ottoman empire collapsed. Across the 1920s its steppe lands, where Bedouin animals grazed, were divided into new political units, and Britain and France moved in to claim former Ottoman territories. In the 1930s and 1940s new nation states emerged from the retreat of those empires, too – and with them the world of passport regimes, customs controls, and nationalist ideologies. Governments, citizenries, international actors (and norms), and marginalised groups clashed to shape the limits and meaning and of the state itself. Throughout it all, the Bedouin have had to contend with the rise of new forms of political belonging that have straddled and encompassed their own tribal territories, grazing grounds, and kinship networks. They have often played a more active role in this process than our conventional understandings of the region might suggest.

‘Desert Dwellers’, now and then

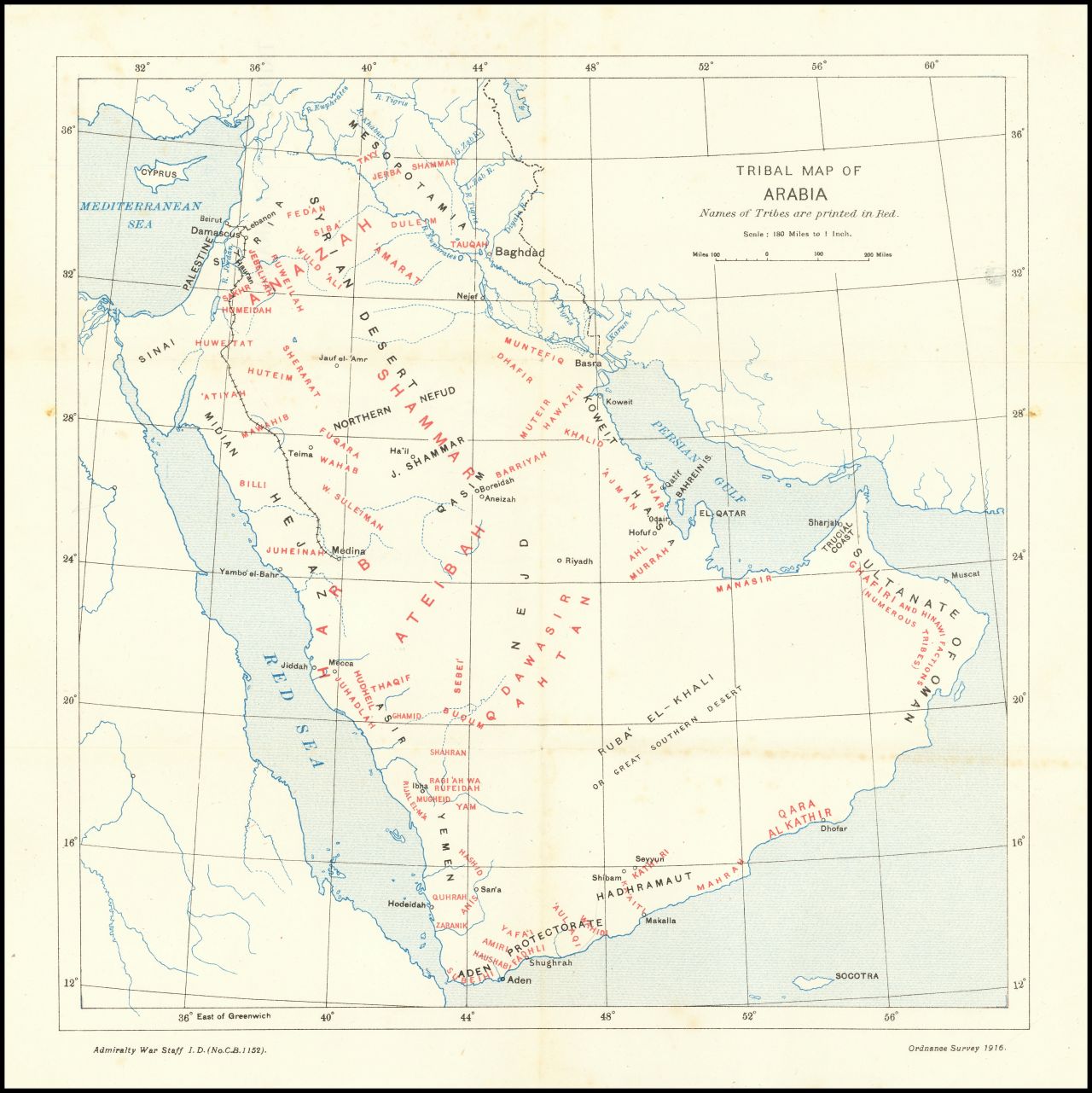

The term ‘Bedouin’ comes from the Arabic Badawi, and can be translated as ‘desert dweller’. Historically, Bedouin groups have been nomadic pastoralists, raising camels and sheep by natural graze on the open steppe of the Middle East. Imagine a great arid and semi-arid triangle, with the Sinai Peninsula as its first corner, Aleppo as a second, and the head of the Persian Gulf making a third. This vast area provides the setting for most of Bedouin experiences explored in this essay; it covers terrain that now lies within the borders of Egypt, Israel, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf states. Between the rivers, towns and agricultural lands of this zone lie extensive areas of low population density, dryland climate and long distances – all these factors have long posed a challenge to state efforts to assert authority. This ‘marginal’ setting – peripheral to urban centres, but not to the Bedouin – has thus contributed both to tensions between Bedouin groups and the region’s states and to political and economic opportunities for the Bedouin themselves.

The Bedouin can fall through the gaps of written histories of the Middle East that focus on its urban populations and national leaderships. Yet evidence of their resilience and adaptation surfaced repeatedly across this century of change, allowing us to reconstruct some of their modern history – despite the relative silence of their own voices in our written archives. Changes in Bedouin relationships with Middle Eastern states have occurred alongside (and become mixed up in) new international definitions of the ‘refugee’, of statelessness, and of the citizen. For the Bedouin, the question of how to react to new state actors and their political and territorial claims had been growing in urgency since the last decades of Ottoman rule, long before the tumult of mid-century Europe brought statelessness onto the international stage.

While our imaginary arid triangle covers a truly vast area, most Bedouin movements within it were much smaller in scale. The area over which a group ranged was influenced by its dira, or tribal territory: the grazing grounds and watering sites upon which the herd could fall back at the height of summer, and from which they set out in search of pasture with the autumn rains. Unlike a state’s borders, its shape and extent were not fixed, but shifted in response to a variety of factors, including changes in a group’s relative influence, the state of desert politics, market conditions, and rainfall – and it was always possible for a Bedouin group to make recourse to another’s dira by negotiation between their shaykhs. Access to particular wells was maintained by the strength of a Bedouin group’s kinship ties, and even if large and powerful tribes based on segmentary lineage structures are now a thing of the Bedouin’s past, strong kin ties remain part of Bedouin life and identity.

Despite this, it is notable how many modern states – from colonial Iraq to the nineteenth century US to the Soviet Union – have tried to end nomadism and pastoralism, along with the flexible understandings of borders and states that often accompanied it. See, for instance, Caroline Humphrey and David Sneath’s book The End of Nomadism on this question in Southeast Asia, and more from Rob Fletcher on decolonization and nomadism in the Arab world.

Viewed this way, pastoral nomadism is a rational economic activity – and an efficient use of the grassland potential of the steppe. But Bedouin movement was not solely a function of seasonal rhythms. Sometimes it could be both longer distance and longer term, a response to political or environmental opportunities and shocks that contributed to Bedouin tensions with state structures, and would recur in the twentieth century.

Indeed, two of the great camel-herding confederations of our vast steppe region had themselves entered it during several waves of migration from around 1650 to 1900. The Shammar came first, northwards out of Najd (in modern Saudi Arabia) for reasons we do not fully understand, but which may have involved flight from the centralising Wahhabist movement, as well as famine and climate change. They in turn were pushed further north and east across the Euphrates by the ʿAnaza – one of the largest Bedouin confederations, and comprising many tribes that would play pivotal roles in the new states of the twentieth century (such as the Sbaʿa, the ʿAmārāt, and the Ruwala). Their exact size has been notoriously difficult to enumerate, but the ʿAnaza were perhaps 200,000 strong in the early twentieth century. The ʿAnaza confederation was more of an imagined community rather than a singular political entity: a genealogically-meaningful frame of reference for diverse Bedouin groups across what is now Saudi Arabia, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, and the Gulf states.

‘Tribal Map of Arabia’ (1916). Maps like these proliferated in the early twentieth century, as state authorities struggled to fix in their minds the location, size and identity of the main Bedouin groups of the Middle East, and where they lay in relation to their own territorial borders. Source: Admiralty War Staff Intelligence Division. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Pastoral nomadism has played a critical part in Bedouin history, then, but we should not see it as the necessary mark of ‘being Bedouin’. For one thing, Bedouin groups, families and individuals have long practiced mixed economic activities, combining livestock breeding with wage labour, state or military service, and the protection of trade and pilgrimage routes. As we shall see, the rise of new state structures affected all these activities, but not instantaneously, or in obvious ways. Movement, too, could occur for a variety of political, ecological, social, and ideological reasons, and at a variety of levels, from the family up to the clan or – more rarely – the tribe. (It is worth remembering, too, that tribalism and nomadism exist outside Bedouin communities in the Middle East, including among Kurds and Druze who may also inhabit the region’s marginal and dryland spaces – and who have their own complex relationships with states and statelessness).

Today, being Bedouin is also a form of cultural identity; despite an unfortunate tendency in popular discourse and commentary to generalise about Bedouin lives (or to trade in ideal-typical generalizations about ‘nomads’ or ‘tribes’), current scholarship is much more focused on exploring the historical and lived experiences of particular Bedouin groups. For all this diversity, however, it is still possible to sketch approximate phases in the changing relationship between the Bedouin and the state in the twentieth century – and its intersection with wider histories of statelessness elsewhere.

Tribe, State, and Shaykh

In the twentieth century, it became a commonplace for colonial officials and modernisation experts alike to assume a basic hostility between nomads and the state. ‘The desert and the sown’ (the famed Gertrude Bell helped popularise the phrase) were locked in remorseless conflict; the two were even said to be ‘a race apart’. It is certainly true that Bedouin groups often have different dialects from hadr

(urban or sedentary) populations, with further distinctions in styles of dress, or poetry, or housing. But the boundary between badu and hadr is nothing like as hard and fast as the experts of yore insisted. Today we are more likely to stress the Bedouin’s deep historic connections with neighbouring settled societies, not the idea of isolated histories. Bedouin have formed states of their own in the past, as far back as the Bedouin Emirates at Aleppo and Mosul in the late tenth century. By the start of the twentieth century, many tribes had for generations been performing a comparable set of responsibilities and obligations to those that the region’s new nation states would now seek to claim for themselves. With a long historical trend of state actors in the region relying on the Bedouin for frontier defence and to support communications – the Mamluks employed them thus to see off the Mongols in the thirteenth century – Bedouin have long recognised the legitimacy of states, even if they have preferred to manage their own affairs without reference to them.

Bedouin tribes have continued to rely on networks of kinship – both real and imagined – that do not necessarily align with state borders or prerogatives, and which have withstood state attempts to disrupt and suppress them.

Nonetheless, and throughout our period, Bedouin tribes have continued to rely on networks of kinship – both real and imagined – that do not necessarily align with state borders or prerogatives, and which have withstood state attempts to disrupt and suppress them. Undoubtedly, the history of the twentieth century contains moments of heightened conflict between states and Bedouin tribes, as the web of Ottoman districts and provinces was replaced by the separate ‘mandate’ regimes of Britain and France. Tensions were particularly marked during the drives for national independence, modernization, and development in the region after 1945. But there has also been plentiful evidence of reciprocity and interdependence; proof that neither ‘tribe’ nor ‘state’ have existed as the fully formed closed worlds that those terms can suggest on paper.

Take the example of Mithqal al-Faiz, the shaykh of the Beni Sakhr – one of the most powerful tribes in Jordan. Born in the late 1870s, Mithqal made a key contribution to early efforts to build up the state of Trans-Jordan in the wake of the First World War, even as he succeeded in carving out protection for both his personal position and his tribe’s autonomy. Similar stories have been told of Shaykh Fahd ibn Hadhdhāl of the ʿAmārāt in Iraq, for example, or of Nūrī al-Shaʿlān of the Ruwala in Syria. In all cases, the balancing act performed by these remarkable individuals became more difficult as the twentieth century wore on, as national borders, drought, new transport technologies, and new ideologies of nationalism posed ever greater challenges to Bedouin political autonomy.

![‘Sheikh Muthgal [Mithqal] Pasha, seated in his tent while camping near Madaba’ (undated, 1930s). Source: Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, USA, LC-DIG-matpc-15660.](https://statelesshistories.org/assets/uploads/images/_1280xAUTO_fit_center-center_80_none/Fletcher-Rob-Figure-3.jpg)

‘Sheikh Muthgal [Mithqal] Pasha, seated in his tent while camping near Madaba’ (undated, 1930s). Source: Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, USA, LC-DIG-matpc-15660.

Indeed, one way to chart the shifts in the relationship between Bedouin groups and the state in modern times is to consider the changing power of Bedouin shaykhs. In the final decades of Ottoman rule, the state sought to co-opt small numbers of shaykhs (and the tribesmen, land, commercial networks, and military power they could command) as a proxy for its own attenuated authority in challenging peripheral locations. This in turn provided many shaykhs with access to new resources, helping them to cement their personal leadership over their tribes. After the First World War, the mandatory powers of Britain and France also tended to govern their respective desert peripheries separately from their settled zones, and indirectly, so that the shaykhs’ relative power over their tribes grew even more. This is the era popularly remembered among Bedouin today as the zaman al-shuyūkh, ‘the age of the shaykhs’. During the 1940s, however, the growing capacity of Middle Eastern states saw them begin to increase their direct contact with ordinary tribesmen, providing access to opportunities and resources beyond the patronage of the shaykh. Fitfully at first, states became more interested in extending basic welfare provisions to nomadic groups, including education and health care, so that functions long within the shaykhs’ remit were now being assumed by state agencies. Shaykhs everywhere had to contend with better educated tribesmen, government policies, offers of direct employment, and centralising state ideologies. Even so, while Bedouin today routinely observe that ‘the age of the shaykhs’ is over, individuals of Bedouin ancestry continue to play prominent roles in local and indeed national politics.

After the Ottomans: the Bedouin and the Mandates, c. 1914-1945

While the Ottoman state had sought to expand its authority over its desert frontiers from the mid-nineteenth century – building forts, despatching troops, establishing new settlements of Circassian and Turkmen refugees – it continued to afford tribal leaders recognition, subsidies, and privileges in lieu of its own ability to monopolise control. Bedouin practices of collecting protection payments or tribute (khuwwa) from villagers, travellers, and less powerful pastoralists continued; Ottoman campaigns to curb them were incomplete before the outbreak of the First World War. Indeed, when the great crisis of the Ottoman empire came – a crisis that would have such lasting consequences for the region’s nomadic pastoralists – the Bedouin were no mere bystanders. Bedouin fought on both sides of the First World War, and some of the Bedouin elite engaged with the ideals of Arab nationalism in opposition to Ottoman rule.

The so-called mandate system involved the British and French colonial occupation of Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Transjordan, under the supervision of the League of Nations. Theoretically, it was supposed to be a temporary state serving as a kind of training for eventual independence. In practice, it largely functioned like old-fashioned racial colonialism.

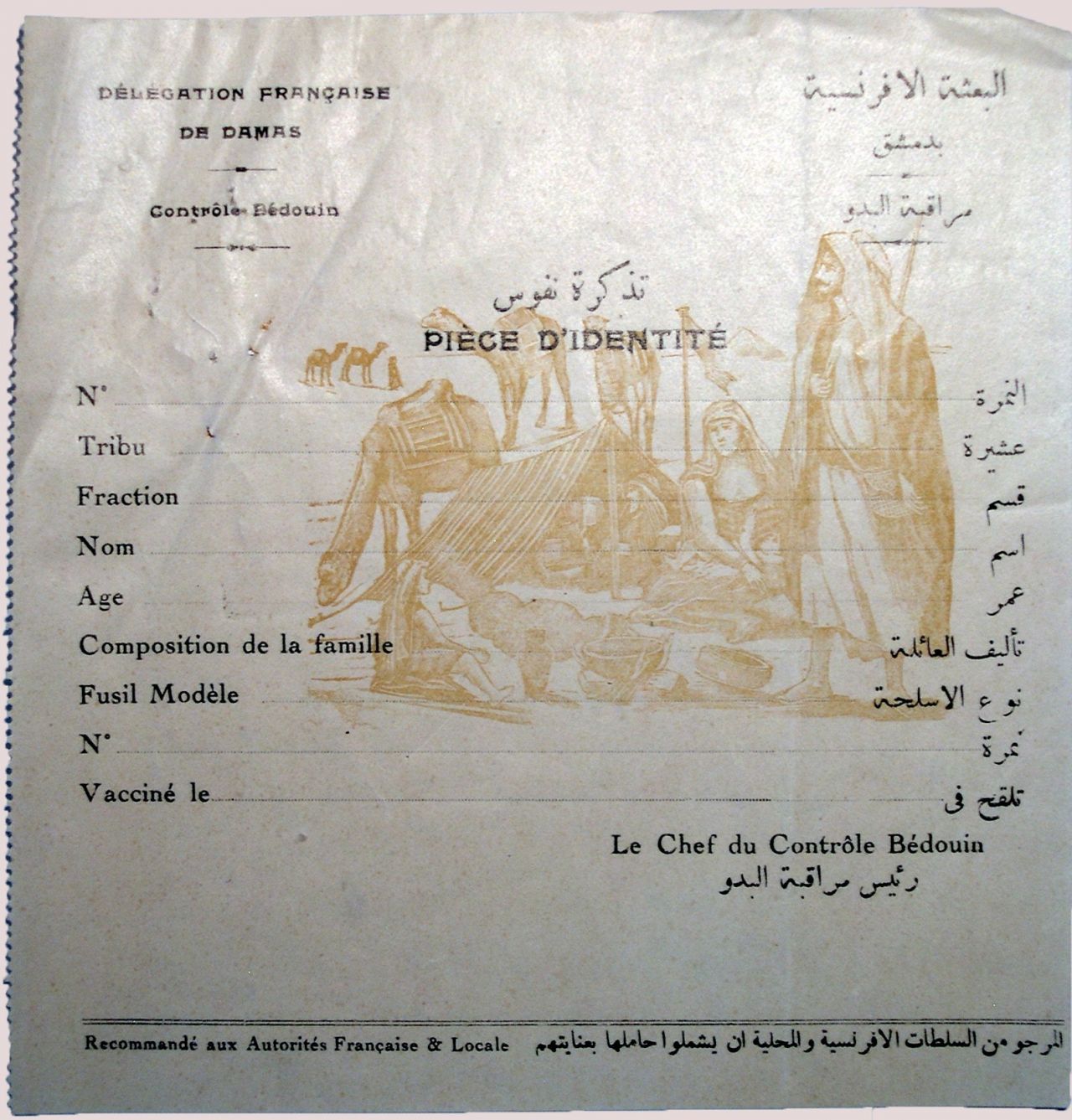

When the Middle East was divided into ‘mandate’ territories under colonial rule (with France claiming Syria and Lebanon, Britain controlling Palestine, Trans-Jordan, and Iraq), its new overseers initially continued many Ottoman policies toward the Bedouin. But the steppe’s new administrators were able to exercise greater territorial control than the regime that preceded them. Colonial programs of land reform, for example, saw communal lands increasingly pass into private hands, so that favoured Bedouin shaykhs became some of the largest landowners in given nation states. Both Britain and France experimented with separate administrative (often paramilitary) governing structures for their ‘desert areas’. In some states, attempts were made to enforce a kind of internal border along the ma’mura, the transitional zone between agricultural and grazing areas. As part of this, Bedouin nomads were increasingly recognised by the state as such, afforded a degree of bureaucratic existence that was more rigid than what had come before. Exempted from full citizenship, ‘nomads’ might be granted some additional rights (such as the right to retain their firearms, or exemption from certain forms of taxation), but denied others (such as direct participation in elections). In practice, if not de jure, they might fall under forms of military law, as well as state-sanctioned versions of ‘Bedouin customary law’.

Bedouin identification papers (1920s). Issued to a small number of shaykhs and ‘messengers’, and accompanied by photographs of the bearer, these ID papers formed part of an attempt in the mid-1920s by French security forces in Syria to monitor and regulate Bedouin movements in the mandate. Source: Fonds Syrie-Liban: Cabinet Politique No. 988, FR-MAE Centre des archives diplomatiques de Nantes. Reproduced with permission.

These messy arrangements served to further the Bedouin’s ambivalent relationship with the state as a source of belonging at the very moment of its inception. In Egypt, for example, Bedouin were excluded from serving in the army and denied national identity cards until 1947, long after their other compatriots received them. In general, the fact that many Middle Eastern states were under degrees of formal or informal colonial rule in this period blunted the force of new discourses of nationalism upon the Bedouin. Both Britain and France sought to check the growth of anti-colonial movements in the cities by seeking out potential partners and allies in the countryside – creating both space and opportunities for a good deal of Bedouin autonomy. Both mandate powers were also prepared to exempt the Bedouin from demands and initiatives that might provoke a backlash – to the growing frustration of urban elites in Baghdad and Damascus, for example.

Mobility, however, was the critical factor in preserving Bedouin autonomy between the wars. Time and again, Bedouin groups took advantage of their relative mobility and their ‘peripheral’ location to shift allegiance between multiple sources of political authority. It was their mobility that protected Bedouin rights to bear arms, and that enabled Bedouin withdrawal into the steppe to evade state attempts at their control. It also allowed some ordinary Bedouin to challenge the growing power of their leaders, even at the height of the ‘age of the shaykhs’. Among the ʿAbada, for example, the leadership of Shaykh Barjas Ibn Hudayb became increasingly overbearing and a source of resentment. In 1930, fully half his followers crossed over from French Syria to British Iraq to escape his authority.

Mobility, however, was the critical factor in preserving Bedouin autonomy between the wars. Time and again, Bedouin groups took advantage of their relative mobility and their ‘peripheral’ location to shift allegiance between multiple sources of political authority.

Indeed, the Bedouin’s existence between states led to their being actively courted by the officials of different governments. The Ottoman lands may have been partitioned, but Bedouin relationships and kinship networks still crossed borders. In the 1920s, for example, there was an attempt by al-Shaʿlān of the Ruwala, supported by the Amir Abdullah of Trans-Jordan, to unite the ʿAmārāt-ʿAnaza and the Dahamsha and to create a large united ʿAnaza tribe to better confront the expansionist ambitions of Ibn Saʿūd. It did not happen, but colonial records are replete with examples of state authorities being forced to look on as Bedouin migrated, traded, raided, and grazed their herds with little regard for territorial limits.

And yet, Bedouin movement was predicated upon reliable access to grazing grounds and watering sites, regulated by custom. Their mobility was thus vulnerable to changes in the pastoral economy, disruption to their access to markets and grazing grounds, and degradation of the ecological condition of the steppe. Across the 1920s, the region’s governments convened a dizzying succession of frontier conferences, boundary agreements and delimitation commissions to establish new international borders across this dryland space, such as the Treaty of Muhammarah between Saudi Arabia and Iraq (1922); the Uqair Protocol (1923) that revised the same; the Hadda and Bahra Agreements (1925) to regulate that Protocol – and so on. Similar agreements on other frontiers were still being made well into the 1930s (and the enforcement of these agreements another matter entirely), so that we should not exaggerate the immediacy of their impact upon Bedouin movement. Nonetheless, the logic of these agreements was to encourage neighbouring states to compete to identify discrete Bedouin groups and to woo them over to ‘their side’, so as to strengthen that state’s claim to key watering sites, strategic locations, lines of communication and potential resources along its new frontiers. Accusations of ‘seducing the tribes’ flew thick and fast, but many Bedouin groups were able to turn such courtship to their advantage, as did groups of the Sbaʿa over the Syrian-Iraqi border. More broadly, inter-tribal disputes and raiding, if conducted near the frontier, now carried international complications, drawing the attention of state officials to these matters as never before.

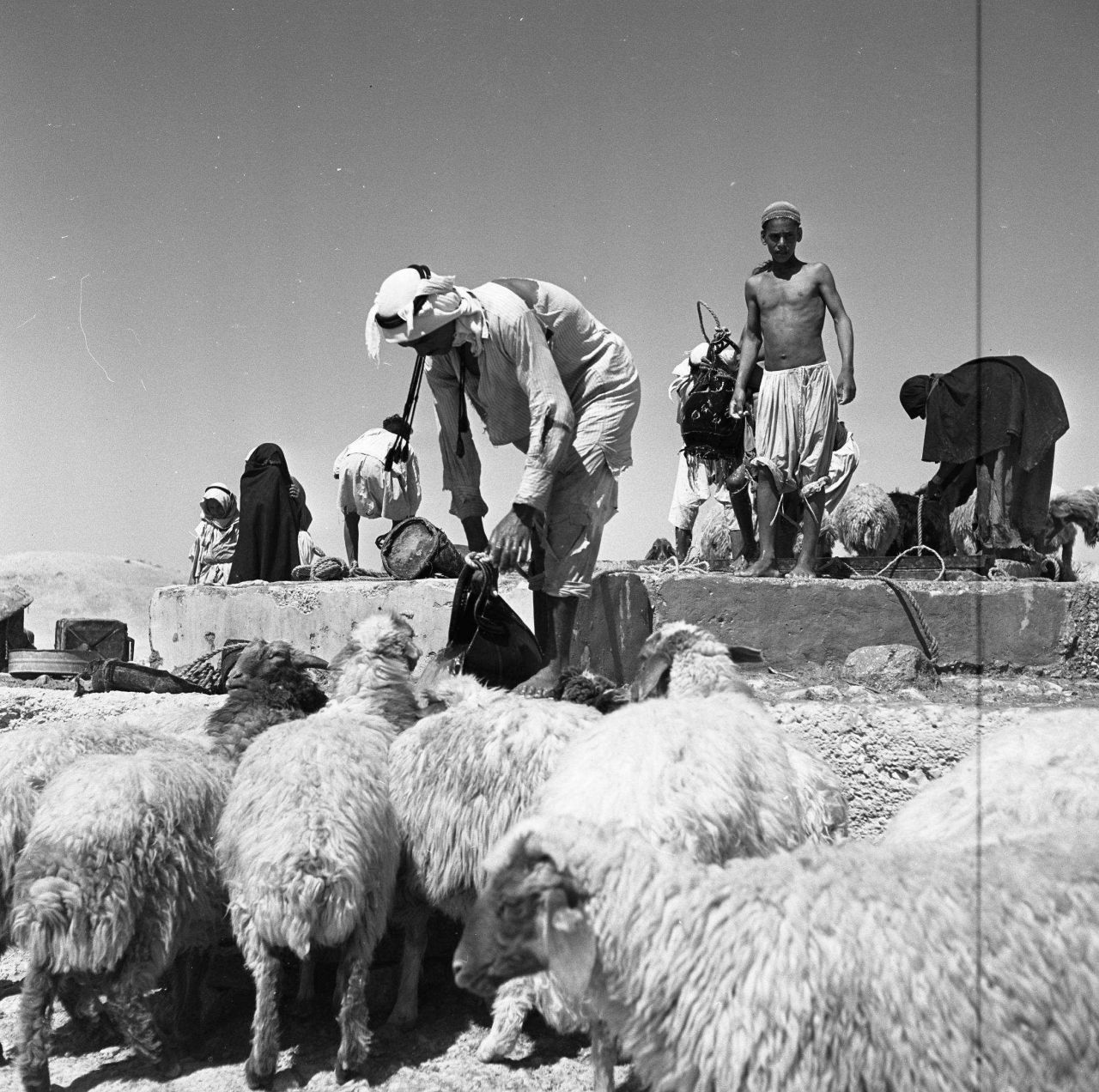

‘Bedouins Come to the Market in Be’er Sheva’ (1955). Source: Eddie Hirschbein Collection, National Library of Israel. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

It was in this context that colonial officials wrestled with the question of ‘Bedouin nationality’. Over the course of the 1920s, the Ottoman empire’s successor states passed Nationality Laws that set out the terms for considering applications for nationality. In the mandates, such legislation was drawn up in compliance with article 34 of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923). In practice, Bedouin had patchy access to such a bureaucratic process, and across the Middle East many tens of thousands would miss out. Instead, the matter of assigning nationality (by whole ‘tribes’, rather than individuals) was often resolved in an ad hoc manner between local frontier officials, and over many years. Efforts were made to trawl old government records and travellers’ accounts for evidence of which nationality was the best fit for each tribe, but decisions often came down to state interests, and hard bargaining. Any solution insensitive to the Bedouin’s far-flung kinship networks and migrations was necessarily less than satisfactory. These officials were not unmindful of the headaches this could cause.

The case of the Beni Atiya is illustrative in this regard. In July 1932, a party of Beni Atiya crossed Trans-Jordan’s southern frontier and raided twelve herds of camels in the Hijaz. Caught and deprived of their loot by Saudi officials, they nonetheless sought to re-enter Trans-Jordan and take up agricultural work to supplement their income (especially important at that time, with the livestock market badly hit by the Great Depression). When the local frontier officer granted them entry (causing Saudi complaints and some embarrassment among his superiors), officials were asked to report on the general applicability of ‘nationality’ to Bedouin tribes. The first report recognised the incongruity of applying nationality to whole tribes, but maintained it could be done, based on the traditional location of that tribe’s dira; or the country in which they had spent the bulk of their time over a recent fixed period; or in which their shaykhs owned any cultivated land; or to which they had most often presented petitions or requests for assistance. A second report rejected the concept of tribal nationality outright, as incompatible with both broader ties of custom and tradition, and the demands of seasonal migration. At any rate, assigning nationality posed near insuperable challenges. Did a tribe’s agricultural land need to be actively cultivated to count as a marker of its nationality? Were trans-border migrations to be actively resisted - by force, if necessary? If members of a tribe cultivated land in one country, but the bulk of the tribe was in another, were they to be issued different nationalities? (Yes, seemed the answer to that question). It is worth noting that these debates ran parallel to shifting institutional definitions of nationality and statelessness in Europe at the time, but with little obvious connection: these decisions were to be made by local officials and their superiors at headquarters, with no conscious reference to wider frameworks.

Assigning nationality posed near insuperable challenges. Did a tribe’s agricultural land need to be actively cultivated to count as a marker of its nationality? Were trans-border migrations to be actively resisted - by force, if necessary? If members of a tribe cultivated land in one country, but the bulk of the tribe was in another, were they to be issued different nationalities?

Ultimately, some (but not all) the Beni Atiya were ejected from Trans-Jordan, more because doing so served British interests than because of any sudden clarity over the Bedouin nationality question. Such ad hoc decisions continued to be made across the interwar years, and their fallout had real impact on Bedouin lives. One Beni Atiya tribesman named Sulaiman ibn Jerad, for example, had enlisted in Trans-Jordan’s armed forces – a time-honoured form of work for Bedouin, which seldom mapped neatly onto ‘nationality’. When, in 1933, he sought to visit his ailing mother in the Hijaz, he found his entry forbidden. Saudi officials pointed to their new Nationality Law; those in Trans-Jordan considered it a vindictive act.

Frontier Violence and ‘the Tribal Question’ in the Making of States

Bureaucratic imperatives to fix ‘nationality’ might have made little progress, however, without the pressing threat of violence forcing the Bedouin to take sides. The key context here was the territorial ambition of King Ibn Saʿūd, and his decision to put Bedouin politics at the centre of his strategy of expansion. As the British and their Hashemite allies consolidated their hold over Palestine, Trans-Jordan and Iraq, their possessions formed a connected arc of territory from the Persian Gulf in the east to the Mediterranean in the west. Ibn Saʿūd – a fierce dynastic rival of the Hashemites, and claiming the allegiance of the many ʿAnaza tribes inhabiting this area – felt increasingly boxed in, and was prepared to use force to coerce that allegiance if necessary.

Beginning during the First World War, and continuing into the early thirties, a low-intensity border war blighted Ibn Saʿūd’s frontiers with Kuwait, Iraq, and Trans-Jordan. Several hundred Bedouin lost their lives (and tens of thousands of animals were taken) on Iraq’s southern border between 1927 and 1930 alone. The threat of raids (and of a new, more violent character) forced many Bedouin groups to acknowledge state authorities and relocate one side of a border or another for protection – decisions they might otherwise have sought to resist for longer.

Formally, the only refugees in the Middle East recognized as such by the League of Nations were Armenians and various Assyrian communities – all Eastern Christians displaced in the First World War.

Here, too, the case of the Bedouin intersected with wider European discussions about the status of the ‘refugee’. While officials in the mandates widely reported the evidence of Bedouin dispossession, distress, and plight before them, they seldom afforded the Bedouin official recognition as refugees, despite their displacement across borders and their apparent lack of state protection. In this, they were not alone. Throughout the period of mandatory rule in the Middle East, the category of ‘refugee’ continued to be reserved for unarmed and Christian communities. Despite the considerable amount of cross-border flight from violence at this time, Bedouin ‘refugees’ were seldom addressed explicitly in mandate reports to the League of Nations. Some groups, such as the notorious ‘Shammar refugees’, were afforded protection in Iraq, only to be relocated again when they would not refrain from counter-raiding into Saudi territory. (They later relocated to Saudi Arabia anyway, in response to the King’s overtures.) Others claiming protection were deemed altogether too hot to handle. Despite insisting that their arrival on the borders of Kuwait constituted ‘the migration of a nation’, the Ikhwan tribes – once Ibn Saʿūd’s most committed followers, now defeated in a rebellion against him – were stopped at the border and turned back into the waiting arms of the King.

The Bedouin and the Nation-State since 1940

By the end of the interwar period, these factors were working to pull Bedouin groups towards one of the region’s states. Among the ʿAnaza, for example, the Fad’an, Ruwala and Sbaʿa were increasingly regarded as Syrian tribes; the ʿAmārāt, in contrast, as Iraqi (though large numbers of them had remained in Najd, and even more would relocate there in the 1950s). These factors coincided with the growing administrative and bureaucratic capacity of the state, and the increase in its direct connections to ordinary tribesmen. (In Saud Arabia, for example, government housing programs and bank loans assisted the settlement – or ‘sedentarization’ – of Bedouin groups).

Fundamentally, the colonial powers had tended to view ‘the Tribal Question’ as a matter of frontier security. Their nationalist successors were more resolved to make citizens, and more suspicious of Bedouin trans-border nomadism and kinship networks. Fired by ideologies of national modernization, they resolved anew to curb Bedouin autonomy. In Israel there was widespread expulsion of Bedouin groups in 1948, followed by their relocation to areas of military control, and new restrictions on their crossing borders. In Saudi Arabia the resounding defeat of the Ikhwan rebels had increased the hand of the state and worked to encourage the Bedouin to settle. (Given the historic role played by Bedouin women in caring for sheep and goats, settlement has generally worked to set new limits on women’s lives). In Iraq, the situation for Bedouin became increasingly difficult after the 1958 revolution, and amidst tightening restrictions on the Iraq-Saudi border.

Critical to this marked uptick in tensions was the prevailing development ideology of the day, which painted pastoral nomadism as economically backward and environmentally dangerous: a classic example of ‘the tragedy of the commons’. New international actors such as the Arab League, the International Labour Organisation, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and the Food and Agricultural Organization gave external validation and support to these prejudices, many of which persist among educated classes, and among the public, today. Few national governments in the postwar period have recognised Bedouin rights to land, which is regularly claimed for military, infrastructural or developmental purposes. In this sense, many Bedouin groups have become landless rather than stateless, alienated from their pastures and water sources, and treated as ‘other’ by their own governments.

Critical to this marked uptick in tensions was the prevailing development ideology of the day, which painted pastoral nomadism as economically backward and environmentally dangerous: a classic example of ‘the tragedy of the commons’.

The impact of the state’s newfound hostility to the Bedouin was particularly apparent in Syria. There, the commitment to the permanent settlement of the Bedouin was actually written into the 1950 Constitution. 1952 witnessed the first round in an ambitious land reform program intent on the abolition of customary land tenure. 1958 brought the union with Egypt and the formal annulment of the legal status of Bedouin tribes: all were now to be citizens, under the common law. From 1963 the Ba’ath Party identified ‘tribalism’ as an anachronistic and anti-national threat; lands belonging to Bedouin shaykhs were expropriated and used to help drive forward sedentarization schemes. Little wonder that significant numbers of Bedouin responded to all this – and to a catastrophic drought in the late 1950s and early 1960s, which decimated herd numbers – by crossing over into Saudi Arabia or the Gulf, as did numbers of the Fid’an and Sbaʿa at this time. In some cases, this has led to the Bedouin groups that remained in Syria having good financial and kinship connections with Saudi and Qatari authorities beyond the boundaries of the state.

The bidun have recently been the object of a plan to permanently deny them citizenship by forcing them to take a nominal Comoros Republic nationality, a story explored in Atossa Araxia Abrahamian’s recent book The Cosmopolites: The Coming of Global Citizenship.

Not all have been able to operate trans-nationally with such success, however. Some Bedouin, having never been issued with state papers or registered as citizens, have found themselves in an increasingly precarious position. In Kuwait, the 1959 Nationality Law conferred citizenship upon urban residents more readily than pastoral communities, a reflection of long-standing prejudices among hadr town residents against the badu who lived beyond the old city walls. Many Kuwait Bedouin struggled to meet the threshold of documentary proof that their ancestors had indeed been settled in the country since 1920; only around half its Bedouin population received citizenship. These bidūn jinsiya (‘without nationality’) have become one of the most infamous cases of statelessness in the region, and while not all bidūn are Bedouin (and not all Kuwait’s Bedouin are bidūn), it has been the growing securitisation of desert border spaces in recent decades – and the concomitant suspicion surrounding those with potential ‘cross-border’ loyalties – that has drastically exacerbated their plight. (Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have significant bidūn populations too, their naturalisation – or its refusal – open to manipulation by individual governments).

Police violence at a Bidoon community protest in Kuwait in 2012. Source: © Greg Constantine, via www.nowherepeople.org. Reproduced with permission.

During the Iran-Iraq war, the bidūn faced accusations of disloyalty and of having suspect connections beyond the nation; they were administratively expelled and relabelled “illegal residents”. In the wake of the First and Second Gulf Wars they have faced sharp reductions in their rights and access to employment and benefits, and subjected to a range of coercive strategies, including arrest and forced deportation. Today the bidūn number is about 100,000. All but a few of Kuwait’s main Bedouin tribes have a number of bidūn among them, denied the right to state education, or to own land, and forced to find work in the informal economy.

Post-Nomadism and ‘Being Bedouin’

Many Bedouin groups and individuals, however, have found employment and a place within the boundaries – and indeed within the official ranks – of the region’s states. In Jordan, beginning in the early 1930s, armed service became a crucial medium through which numerous groups became reconciled to the central government, and the sons of prominent shaykhs, including of Mithqal al-Faiz, have served as important advisors to the King. In Kuwait in the 1970s the ruling family introduced tribal groupings into Parliament to serve as a loyalist bulwark, and though they have provided some opposition in recent years, they are nonetheless oriented within the parameters of the state. Even the most assertive regimes have relied on Bedouin co-operation. In Syria, President Hafez al-Assad called on Bedouin leaders to assist in blockading the town of Hama during the 1982 Islamist uprising, leading to a closer relationship with the state in the years that followed.

Such relationships have tended to bring into being more formalised conceptions of ‘tribe’ and of tribal identity today, but often alongside a sense of belonging oriented toward the nation-state, rather than in lieu of it. At its clumsiest, this has taken the form of attempts to repackage ‘Bedouin culture’ as a commodified component of a national heritage, including in folklorist tourist exhibits.

At its clumsiest, state incorporation has taken the form of attempts to repackage ‘Bedouin culture’ as a commodified component of a national heritage, including in folklorist tourist exhibits.

And yet tribe remains a compelling fact of life for many Bedouin, and for those who still live far from the region’s towns and cities, the state’s laws, taxes, proscriptions, and interventions can seem very remote indeed. In many such areas, Bedouin customary law is still in use among Bedouin communities, and de facto communal land ownership practiced. The internal combustion engine has allowed some families to provision their herds even deeper in the desert; many more might maintain small herds remotely, as absentees. Where kinship networks cross borders, they still serve to present Bedouin with options in times of distress: in 2003 many Iraqi Shammar moved their herds into Syria, and then into Jordan and Turkey when displaced again by the civil war. (Bedouin have also played important community leadership roles in that conflict, on both sides).

Today, practicing pastoral nomadism features much less prominently in local self-identity than a sense of belonging to a certain clan or tribe, so that scholars are increasingly fascinated by the phenomenon of ‘post-nomadism’: of how a sense of ‘being Bedouin’ has circulated long after groups have taken up settled life. For, despite the means at the nation-state’s disposal, the mid-century assault on Bedouin autonomy was incomplete: the strength of kinship ties, dialect, and culture of many Bedouin groups has proven remarkable. In Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, sedentarization and urban living has been accompanied by a marked uptake in the use of tribal names as surnames – and often with reference to the largest tribes, rather than particular clans. New ‘Bedouin’ and ‘tribal’ identities have made their mark in the Arab public sphere since the 1980s, and social media platforms today circulate old photographs of shaykhs, and new poetry. Being Bedouin is increasingly a social identity shared by people who now dwell in cities and towns, and whose only connection to herding is by ancestry, or heritage. Nonetheless, many Bedouin have been marked by the experience, over generations, of ambivalent relationships with the region’s states. Their stories may still reflect on that history – and on current affairs – from a very different perspective from that of the authorities.