January 24, 2022

Transitional Statelessness: Drugs, Disease, and Denial of Refugee Care in the New State of Pakistan

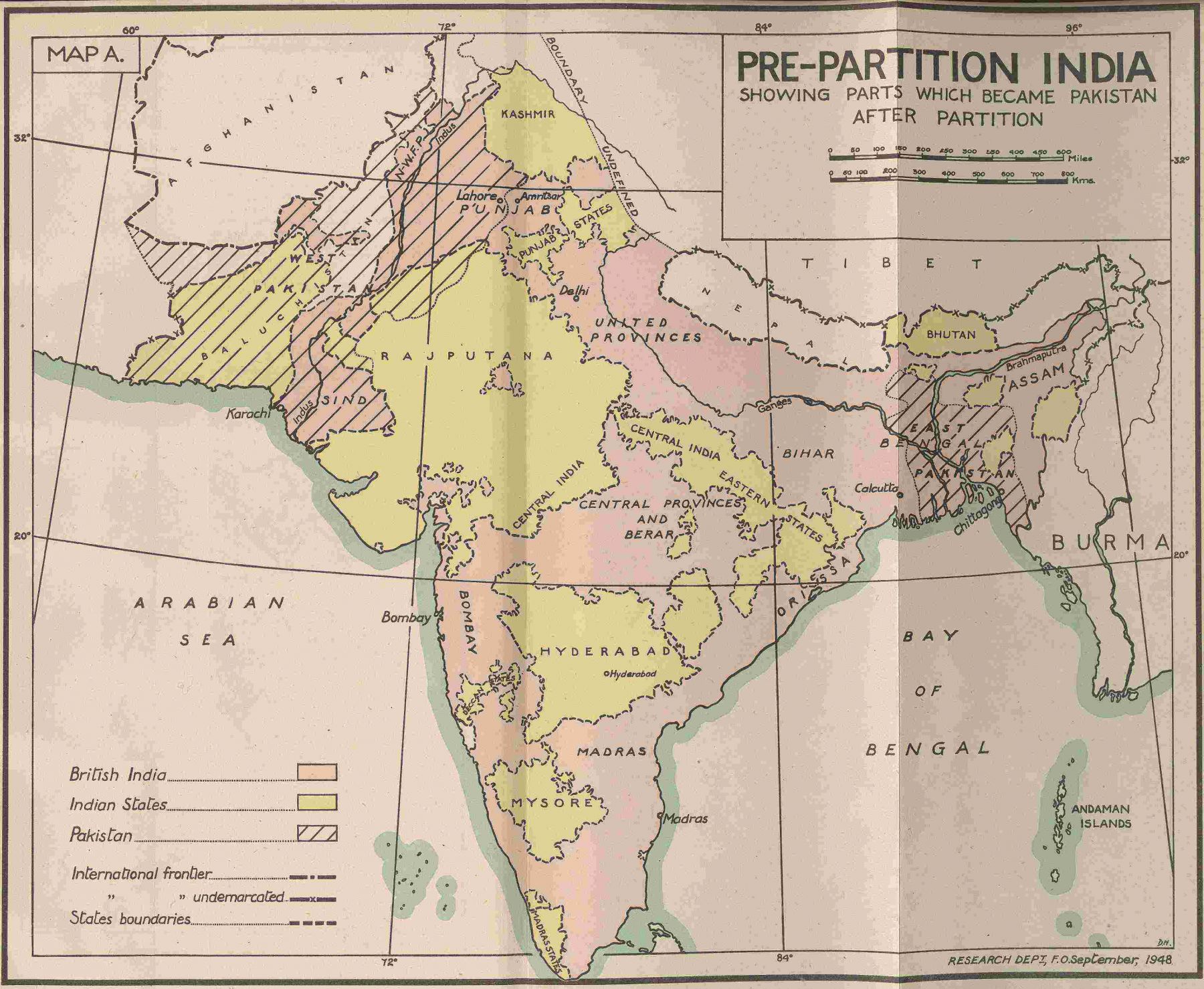

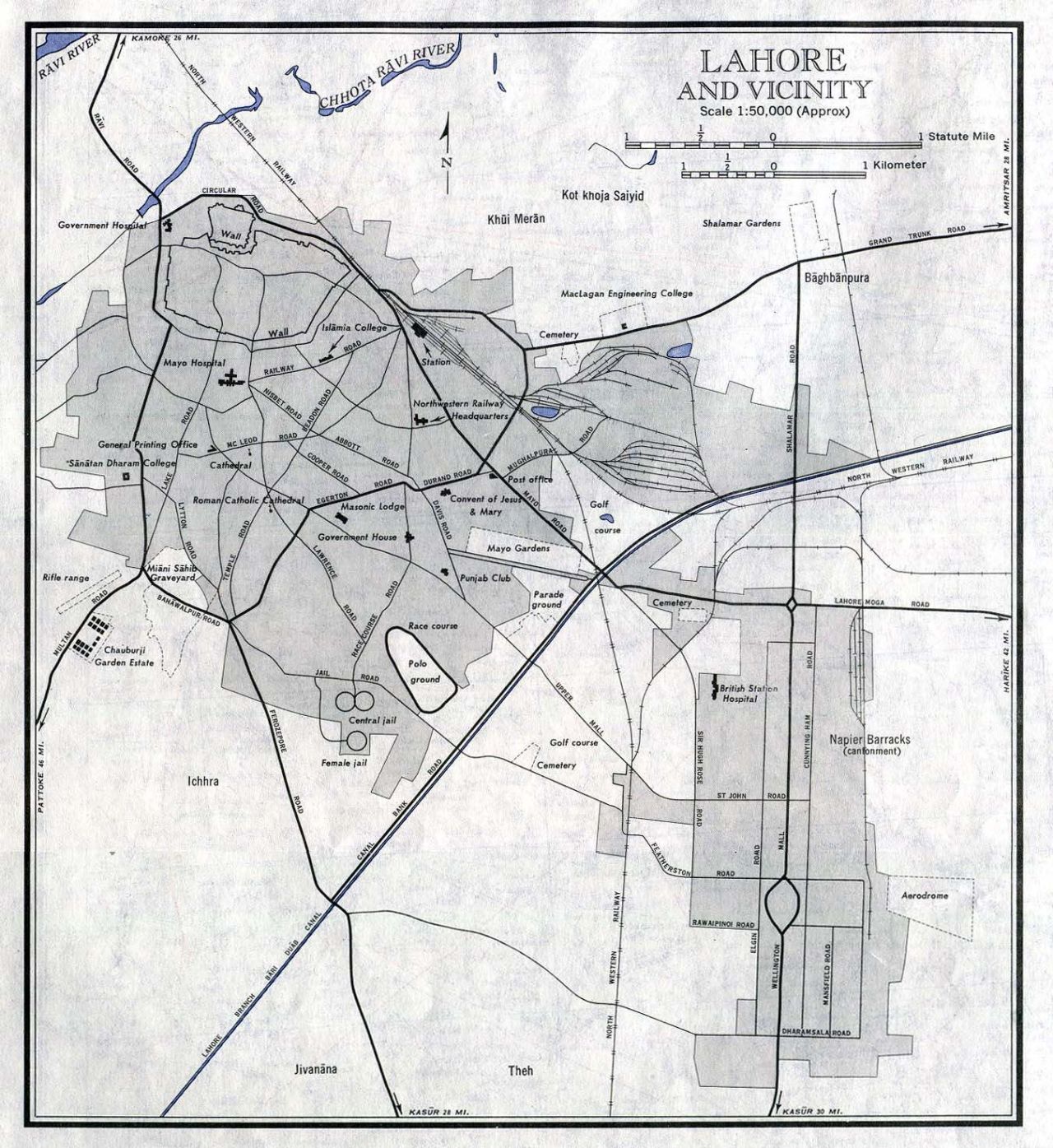

The movement of people from what would become India to what would become Pakistan started a few months before the partition of the subcontinent on August 14th 1947 and peaked in the weeks immediately after the formal declaration. The flow of people went in two directions: Muslims opting for Pakistan moved outward (towards West Punjab and East Bengal) and Hindus and Sikhs moved inward - though many Muslims stayed in India, and a smaller percentage of Hindus and Sikhs also decided not to move. In September and October 1947, newspapers in Pakistan reported as many as 25,000-50,000 migrants arriving daily in Lahore alone. This number stayed in the tens of thousands for several weeks, and while the numbers did come down starting in the spring of 1948, partition-related migration would continue for nearly two decades.

Pakistan’s first constituent assembly (CA) started soon after the birth of the nation, but unlike India – which came up with a constitution in 1948 – Pakistan’s first constitution was not ratified until 1955.

In the formal, European-derived legal sense, those who were migrating to Pakistan were not stateless. But the all-important questions of who counted as Pakistani and indeed what citizenship itself would mean were as yet unanswered. Passports for Pakistani citizens were not introduced until 1952. Land rights for those who had moved into the new country were tenuous for years to come. In theory, the newly arrived migrants were citizens like those who were already present on those lands. In reality, however, the rights of those who had migrated were not equal to those who were already present. This transitional statelessness, both in time and in place, manifested itself in several civic spaces. Public health was one of the most visible.

The rights of those who had migrated were not equal to those who were already present. This transitional statelessness, both in time and in place, manifested itself in several civic spaces. Public health was one of the most visible.

Although nominally entitled to citizenship in the new state of Pakistan, Muslim refugees arriving from India experienced limited access not only to passports but to basic health services necessary for their survival. The public health arena thus illustrates how political experiences of statelessness can become physical ones – perhaps especially when the state itself operates with confusion about its responsibilities or abdicates its role outright. This abdication of state responsibility for health services had long-ranging implications for both the state and the newly arrived refugees. These implications went beyond the immediate and tragic loss of life and contributed to a longstanding distrust between refugees and the state, which manifested itself in the rise of subsequent relationships and political movements led by migrants, refugees and their descendants. An examination of the experiences of migrants coming into the Pakistani province of (west) Punjab in the immediate aftermath of partition – the moment of greatest migrant movement – illuminates the long-term consequences, both political and physical, of the experience of transitional statelessness in 1947-48.

University of Texas, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection

An Absent State? Transitional Statelessness through the Lens of a Public Health Crisis

While some of the migrants had the resources and family connections to move with their families and relatives, a very large number (probably several hundred thousand) found themselves in various refugee camps along the new border that separated east Punjab, now in India, from west Punjab, now in Pakistan.

To date, there has been no study or even estimate of how many people died during migration. Even the number of migrants remains controversial and disputed. This is in part due to poor data gathering and reporting, and in part due to large number of the dead who had no identification, or family in west Punjab. The Pakistan Times ran a regular column (sometimes giving it as much as half a page) called “Refugee Corner,” starting in September 1947, where concerned family members would request information on their loved ones who had gone missing. Estimates have been made in specific camps, but an overall number remains elusive.

These refugee camps were constructed on an ad hoc basis, often repurposed from the barracks used during the Second World War. Most offered little real shelter and no real medical services. As a result, refugees also set up makeshift camps by the sides of roads choked by large caravans of arriving migrants. In this environment, there were several disease outbreaks, the most notable of which was a terrible cholera outbreak that continued for most of the fall of 1947 in Lahore and other parts of Punjab. Malnutrition, combined with exhaustion, was rampant and probably contributed to excessive mortality among the refugees. While the central and provincial government made several claims that the epidemic was subsiding, the reports from nurses, doctors and local volunteers painted a different story. To make matters worse, the fall and winter of 1947 were severe, and in the absence of adequate shelter, warm clothes, or blankets, mortality from hypothermia was also high. At times, as many as four hundred migrants died on a single night on the Ferozepur road that connected east and west Punjab.

US Army Service Map of Lahore, 1963, showing Ferozepur Road leading south-west (University of Texas, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection).

The absence of medicines, warm clothing, shelter and lack of medical staff was frustrating for refugees who had expected a more organized and empathetic state. Migrants who were shifted to hospitals were dismayed to be charged enormous sums for treatment, which was supposed to be free of cost. The public health crisis was therefore among the first challenges faced by the refugees and migrants in the new state, which they found both lacking in organization and support.

Pictures of the camps are available through a valuable citizen archive project.

Public health space, unlike land distribution or housing which were domestic matters, was inherently an international space involving aid agencies, foreign missionaries, and local volunteers. There were dozens of foreign nurses and doctors; some had worked in the region before, during the Second World War or during prior humanitarian disasters in the region, and some had just arrived in response to the appeals from the government of Pakistan. The new government not only allowed these foreign workers to come but actively courted international agencies for supplies, logistics and personnel support. The observations of these foreign workers through their diaries, letters and reports, most of whom were from western Europe and the US, were not subjected to the same censorship that the local press was experiencing. This international angle gives us some independent evidence of the crisis on the ground and provides narratives that contrast with the official position of the government; importantly, international aid agency workers also sometimes recorded the perspective of the transitional stateless communities themselves, who found few other outlets to share their grievances.

The fall and winter of 1947 were severe, and in the absence of adequate shelter, warm clothes, or blankets, mortality from hypothermia was also high. At times, as many as four hundred migrants died on a single night on the Ferozepur road that connected east and west Punjab.

State’s Response

The state’s response to the mounting health challenges faced by refugees illustrates how the fledgling government struggled to fulfil what it viewed as its own formal responsibilities. On one hand, the state actively downplayed the health crises and projected a narrative of success and winning the battle for independence and freedom. The minister for refugees spoke about unprecedented hospitality of the state and residents of Lahore in particular and Punjab in general. The state’s approach was not driven by the hospitality or empathy that it exhorted its citizens to practice – rather it was characterized by its own need for security, authority, and international image control. Newspapers that were either under state control or were aggressively engaged in self-censorship featured full pages of pictures showing grateful refugees embracing their hosts. At the same time, the government sent repeated requests for international aid, both in terms of financial assistance and qualified personnel including putting out ads not just in local newspapers but also in the foreign press (e.g. British newspapers). The government openly courted and welcomed support from several missionary and humanitarian organizations. Unlike property or housing issues, which were squarely an internal matter, public health and disease control was seen as a global humanitarian problem. There was also a gendered dimension to this health crisis, which was considered a problem best dealt by women; newspaper columns called “Women’s Corner” focused on how the general public could support refugees in their struggles. Fatima Jinnah, the sister of Pakistani governor general Muhammed Ali Jinnah, and various wives of prominent politicians would visit the various refugee camps and emphasize the need for support and empathy – usually without discussing rehabilitation, shelter, or refugee economies, all the purview of male public figures.

Jinnah had served as the long-term leader of the All-India Muslim League, and became the first Governor General of the new state of Pakistan upon its founding in 1948. His career was marked by a degree of ambivalence about the project of an independent Indian Muslim state, which he came to support only at the very end of the Raj, in the 1940s. The best account of his complicated career is still Ayesha Jalal, The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League, and the Demand for Pakistan.

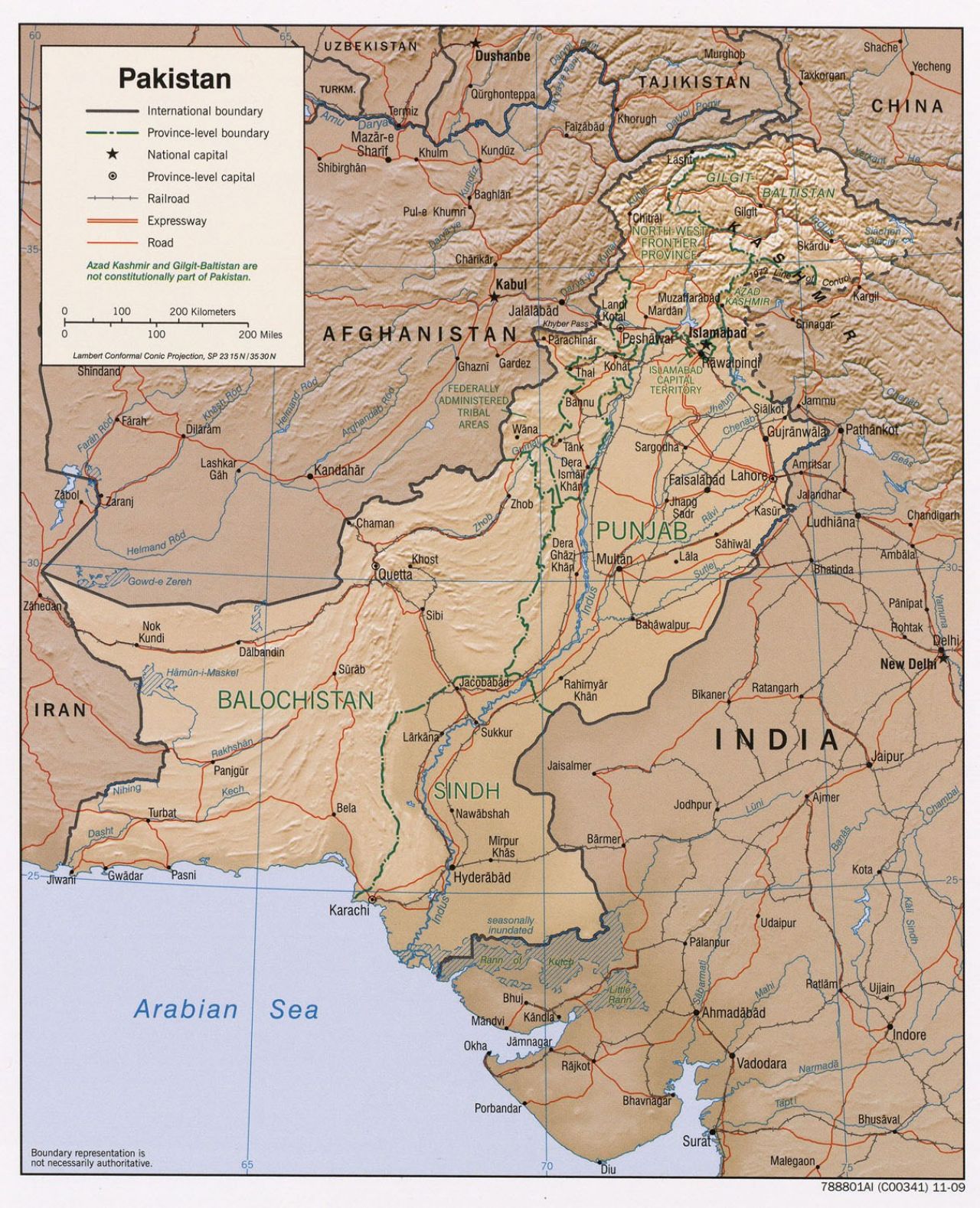

While the outward face of the government embraced a state commitment to hospitality and empathy, the internal feeling was that the refugees represented a heavy burden. There was constant disagreement between the central government and the provinces about allocation of resources. The southern province of Sindh continued to push back against any efforts to relocate refugees from Punjab – a rejection that weighed heavily on refugees, who developed a long-term distrust of the Sind government. Despite celebrating itself as the refuge for Muslims in India who wanted self-determination, the state also now began to actively push back against welcoming new refugees – suggesting that Indian Muslims should stay in India and offer their unflinching loyalty to that state. For political and communal reasons, the state also prioritized rehabilitation and integration of refugees who came from the part of Punjab that was now part of India, versus those who came from other Indian states such as Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar. Few new clinics or hospitals were set up in the southern province of Sindh or the western province of Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP, now called Khyber Pakhtunkhwa or KPK), despite the official policy encouraging resettlement in those areas.

The state’s approach was not driven by the hospitality or empathy that it exhorted its citizens to practice – rather it was characterized by its own need for security, authority, and international image control.

By February 1948, the internal mechanism for refugee rehabilitation and support was in complete chaos and the minister for refugees resigned from the committee in charge of refugee welfare, citing irreconcilable differences and the attitude of other committee members. There were also reports of rampant corruption by ministers and the local feudal lords. The refugees themselves were increasingly frustrated – not just with the lack of coordination but also with dire conditions in hospitals and clinics, which were overflowing with patients and routinely ran out of medicines. In this atmosphere of chaos, most support was provided by local residents and volunteer organizations; in the three-part structure that had emerged (international agencies, local volunteers and doctors, and the state), the state’s contribution was often the weakest. In other words, the state’s own approach to hospitality and empathy was in sharp contrast to what it was preaching.

The state’s response was also evident from how it defined healthcare versus what it considered a law-and-order issue: the effects of communal violence between Hindus and Sikhs on one side and Muslims on the other. Public health was largely limited to control of epidemics of infectious diseases and responding to physical wounds. There was no provision for psychological support or mental health. This was particularly evident from the policies designed to recover “abducted women.” Gender-based violence had reached epidemic proportions by winter of 1948; there were week-long organized conferences on how to recover women abducted from villages and refugee camps. The government estimates suggested as many as 50,000-60,000 women had been abducted from refugee camps or the caravans of refugees; the actual numbers are likely much higher. However, the effort fundamentally focused on their physical recovery (with the help of the military), with minimal effort for their reintegration, rehabilitation, and general well-being. Broadly speaking, the issue of systemic violence against women was not viewed from the lens of public health but was seen as a security issue, and an international embarrassment. Because of the prevailing sentiment that the issue of widespread abduction undermined the state’s legitimacy and highlighted its incompetence, shame was more prominent than empathy, support or hospitality as a driver of state policy vis-à-vis transitional statelessness.

Similarly, migrant orphans were viewed as a social and financial liability. They were often handed over to privately run orphanages operating as charities (with some government subsidies), which had very few provisions for healthcare. A systematic study of what happened to the recovered women, or how the orphans were absorbed in various sectors of society, remains unwritten. Gender-based violence, particularly rape, nonetheless became a major topic of Urdu short stories written in the late 1940s and 1950s – many of which were summarily banned by the government and labeled as vulgar, blasphemous, or anti-Pakistan.

Long-Term Implications

While the crisis peaked in late 1947 and early 1948, refugee health challenges continued for years and even decades. The sights of sickly migrants on streets and pavements in Karachi (still numbering around 800,000 in the 1950s) was seen as an embarrassing eyesore. In the political sphere, the distrust triggered by state abdication of refugee health responsibilities reverberated in the many riots and disturbances of these years. Yet there were other, more positive outcomes from the public health crises of 1947-1948 that speak to a changing landscape of statelessness – transient and otherwise – in the newly constituted country: the crisis saw Pakistan’s first mass vaccination campaign against cholera, and had a profound effect on the newly created Pakistan Medical Association and the subsequent national medical curriculum.

The distrust triggered by state abdication of refugee health responsibilities reverberated in the many riots and disturbances of these years.

In the seven decades since the creation of the state, Pakistan has seen two other major episodes of statelessness and cross-border displacement. Unlike the 1947-48 migration, both of these have been viewed primarily through a national security lens. The first came when millions of Biharis and Bengalis became refugees or stateless persons in the aftermath of the 1971 war and creation of the new state of Bangladesh. The state of Pakistan in this instance was far more xenophobic than it had been during partition, and provided few (if any) provisions for basic refugee services including healthcare. The issue – to this date – remains a highly sensitive subject. Given that the state has consistently viewed Bengali migrants with suspicion, it has made very few attempts to engage international agencies in providing health services – a significantly different position from the one taken in 1947-48. Fifty years after the creation of Bangladesh, millions of stateless Bengalis in Pakistan remain without any access to public healthcare.

The other episode was the movement of nearly two million Afghan refugees into Pakistan in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion in December 1979 and the subsequent conflicts in Afghanistan. The recent (August 2021) Taliban takeover is likely to increase the number of Afghan refugees in Pakistan. While the government has had little interest in the social and political integration of Afghan refugees, the approach to public health has been similar to the 1947-48 crisis. Here, unlike the situation with Bengalis, the government of Pakistan has heavily engaged international aid agencies and sought to benefit from highlighting the humanitarian crisis in the region. This does not suggest, however, that Afghans in Pakistan have robust or reliable access to healthcare.

The history of public health provides a useful way to understand the phenomenon of transient statelessness in post-partition Pakistan, simultaneously influenced by an emerging but uncertain state and by the presence, difficulties, and demands of refugees themselves. It tells us something about what the state thinks are basic rights of refugees, and how it came to such positions. This public health lens on Pakistan’s refugee history also illuminates what the state considered matters of health and what it viewed as matters of national security, with such definitions evolving and changing in both time and space. It sheds light, too, on the extent to which the state has balanced the benefits of foreign engagement in its internal affairs versus the necessity of exerting sole control over the political narrative. Finally, it suggests that the category of transitional statelessness – which could describe many displaced and migratory communities beyond Pakistan – should be incorporated into our historical understanding of statelessness as one of the paradigmatic political experiences of the twentieth (and now twenty-first) century world.