January 24, 2022

Problems of Statelessness, Solutions of Citizenship? A Historical View from the Middle East

It is one of the most cherished ideas of internationalist organizations and advocacy groups that citizenship is the antidote to statelessness. Take, for instance, the United Nation’s dramatic declaration of its intent to “end statelessness” by 2024, which relies on the dual premise of assigning stateless people a nationality and ensuring national registration at birth, thereby preventing any more children from being born stateless. This approach dates back to the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights , which in 1948 included nationality on its list of fundamental human rights. The London-based Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion, the primary human rights organization committed to advocacy for stateless people, defines its vision similarly: “a world in which everyone’s right to a nationality is respected, securing inclusion, equality and access to rights for all.” The very language of “problem” and “solution” makes clear how much the internationalist community has understood citizenship as the logical response to dilemmas of statelessness in the modern world.

But such an imaginary – straightforward in theory, if not in practice – of the relationship between citizenship and statelessness tends to fall apart on closer scrutiny, not least because the international community charged with solving the “problem” of statelessness cannot itself enact the “solution” of citizenship. “The entity with the responsibility of rectifying the injustice of lack of citizenship (the international society of states),” writes legal scholar Matthew Gibney, “is not the same as the entity that controls the good that needs to be distributed (citizenship). ... Therefore, to speak of a right to citizenship (or nationality) begs the question: where? Which particular state has a duty to provide citizenship to the stateless person?” 1 In other words, the first issue with this framing is a political one: the problem and the solution, as currently constituted, are located in different political spaces, and the one cannot be reliably deployed to meet the challenge of the other.

The very language of “problem” and “solution” makes clear how much the internationalist community has understood citizenship as the logical response to dilemmas of statelessness in the modern world. But such an imaginary – straightforward in theory, if not in practice – of the relationship between citizenship and statelessness tends to fall apart on closer scrutiny, not least because the international community charged with solving the “problem” of statelessness cannot itself enact the “solution” of citizenship.

In historical terms, too, the relationship between statelessness and citizenship has been far from straightforward. Nineteenth and twentieth century Middle Eastern history offers instructive examples. In some cases, governments sought to rectify statelessness without the provision of citizenship or with versions of citizenship that were unwelcome or detrimental to stateless beneficiaries. The Ottoman Commission on Refugees, for instance, resettled millions of refugees during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries but never made citizenship central to its approach. Internationalists in the 1920s and 1930s handled statelessness in the Middle East and Europe with the “Nansen passport,” a document that allowed for labor migration but explicitly did not confer citizenship. In the post-WWII era, efforts to provide citizenship to huge numbers of newly stateless peoples met with resistance from individuals and communities who strongly objected to plans to “solve” their statelessness via the external imposition of a new nationality. This category included some European Jewish displaced persons who had no option but to take citizenship in Israel after 1948, as well as many of the Palestinians they displaced, who often developed a profoundly ambivalent relationship with their new Jordanian citizenship and declined to advocate for refugee citizenship in other parts of the Arab world. In a more recent era, when citizenship has provided an explicit “solution” to statelessness, its provision was often intended to serve the economic and political interests of the host nation-state rather than the stateless individual. This is famously the case in Kuwait today, whose government has forced a number of its stateless residents (bidun) to take the passport of the island nation of Comoros for reasons that benefit the state and further dispossess the stateless.

The Middle East is a thus useful vantage point from which to survey the historical relationship between statelessness and citizenship, and to understand how this ostensible problem-solution dyad has been deployed by nation states to serve their own needs. Here, we present various permutations of statelessness across the Middle East’s past hundred and fifty years. Such a historical view can help us see how assignments of nationality have failed to solve statelessness, and illustrate how state actors have mobilized the mutually reinforcing phenomena of citizenship and statelessness primarily to buttress their own political and economic interests.

Ottoman Legal Regimes: Statelessness, Nationality, and Land

The Ottoman Empire was among the first modern states to formalize citizenship and statelessness through national legal codes and to envision refugeedom as a formal legal designation. Ottoman legal decrees on refugeedom – encompassing of displacement, denationalization, and statelessness – came first, as early as 1859. It was not until a decade later, in the context of the Balkan wars, that the empire sought to codify nationality. For the Ottoman government, these two bodies of law represented distinct and separate legal regimes having relatively little to do with each other.

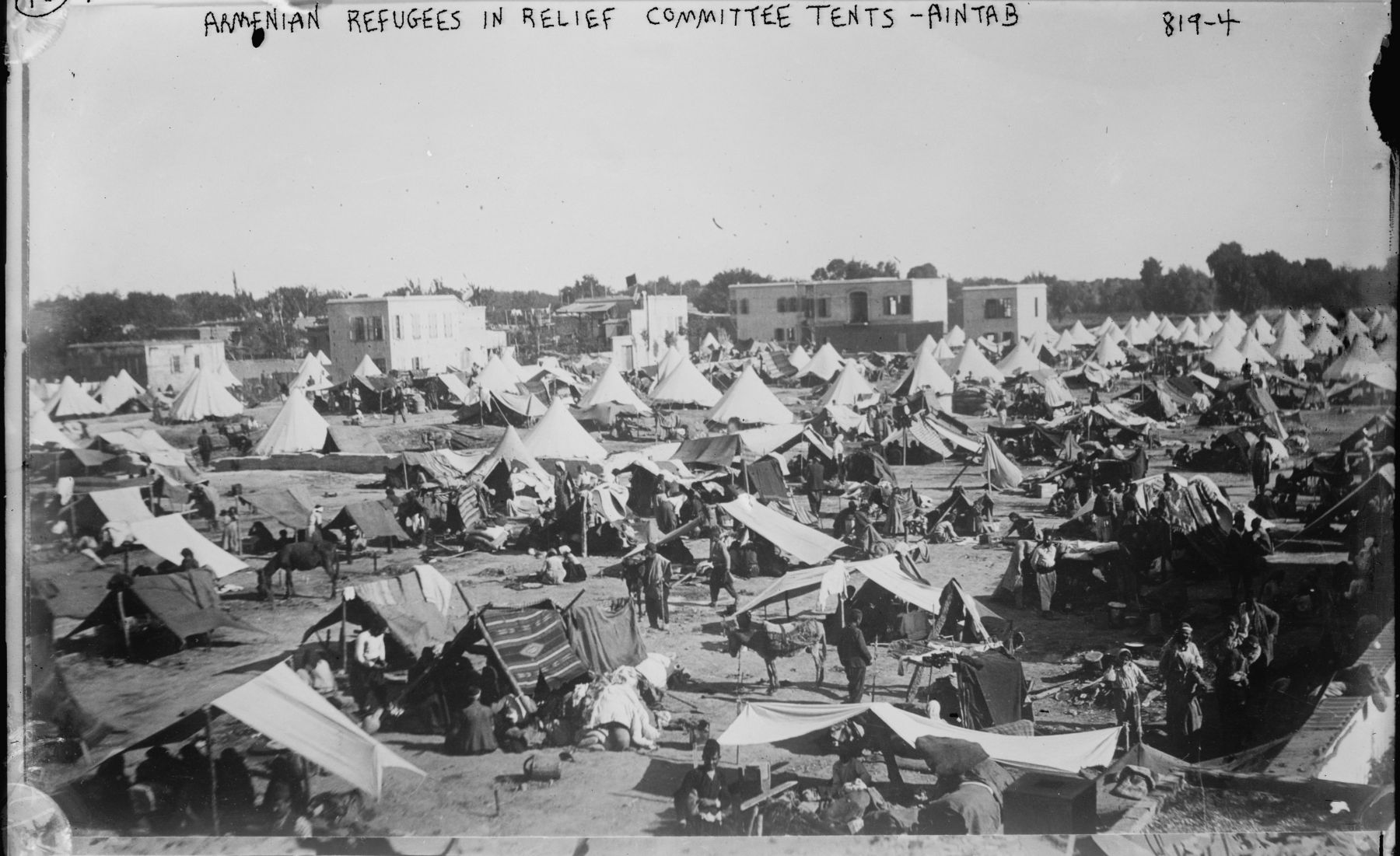

In other words, the Ottoman state conceived of refugeedom and statelessness as imperial challenges essentially unrelated to the issue of defining nationality, and deeply connected instead to state territoriality and centralization. The earliest state-level refugee agency anywhere in the world appeared in the Ottoman empire in 1860, founded to deal with the mass displacement of Muslims from the Ottoman Balkan borderlands and the Caucasus. By the end of the nineteenth century, a series of wars from Greece to Bulgaria to the Crimea had displaced more than a million Muslims from these formerly Ottoman spaces into Anatolia – all now stripped not just of their property and most of their possessions but also of their nationality, as new states like Serbia and Bulgaria denied their claims to citizenship.

The Ottoman response was only very secondarily concerned with the refugees’ national status. Instead, the Muhacirin Komisyonu (Commission on Refugees) dealt with practicalities of resettling refugees, placing them in rural and border areas where they would be less likely to constitute a political problem and could also become active participants in Istanbul’s project of controlling far-flung territory. Consequently, the Ottoman government settled Balkan and Caucasian refugees near the Russian border in the Balkans; in rural parts of modern-day Syria and Jordan; and in places in eastern Anatolia where nomadic Kurdish tribes had resisted imperial incorporation. This Ottoman approach to statelessness was essentially local and practical rather than abstractly political, designed simultaneously to offer humanitarian relief and to use the refugees to bolster state control. Eventually a nationality clause was added to Ottoman refugee law, offering Muslim settlers citizenship after five years and extending citizenship to non-Muslim refugees in certain cases as well. But in the late Ottoman sphere, the “solution” to the “problem” of statelessness was not citizenship: it was land.

Thus, in one of the early incarnations of modern law around nationality and statelessness, the two phenomena were conceived as separate categories, each addressing a specific set of problems for the state without special reference to the other.

Ottoman nationality law, by contrast, emerged neither from political discourse about the rights or responsibilities of citizens nor from questions of displacement endemic to the late nineteenth century. Rather, nationality laws came about in response to the perpetual late Ottoman problem of European and other foreign residents, and their local proteges, claiming capitulatory – that is, extraterritorial – rights. The acquisition of Ottoman nationality could be accomplished, according to the 1869 law, in any one of three ways, still in use for conferring citizenship across the globe today: by descent (ius sanguinis), by birth (ius soli), or by naturalization on the basis of residency. All three of these categories were here configured as broadly as possible, to reduce the likelihood of Ottoman residents claiming capitulatory “protections” as subjects of some other European power. Nationality, in the late Ottoman sphere, represented a tool to protect the state from the depredations of foreign actors who sought to own land, invest in businesses, and act with legal impunity on the basis of their citizenship elsewhere. Thus, in one of the early incarnations of modern law around nationality and statelessness, the two phenomena were conceived as separate categories, each addressing a specific set of problems for the state without special reference to the other.

The Interwar Regime: The Nansen Passport and the Right to Work

In the 1920s, stateless refugees from former Ottoman lands became one of the sites for a scheme that remains, up to the present day, the only major effort to bestow some kind of political status on stateless people via an internationalist organization. The so-called Nansen passport, named after the League of Nations High Commissioner on Refugees Fridtjof Nansen, was a League-issued travel document first developed in 1922 for “White Russian” refugees denationalized by the new Bolshevik regime. It was extended two years later to stateless Armenians from the Ottoman realms. In this internationalist iteration of policy vis-à-vis statelessness, the proffered solution was not the provision of nationality – which would have been anathema to virtually all of the signatories, who were generally engaged in shutting their doors as firmly as possible in the 1920s – but the provision of the right to move in search of work.

The Nansen passport did not guarantee the right to remain or move towards permanent residency or citizenship. Rather, it was designed to assuage the concerns of unwilling host societies by permitting migratory refugee labor: holders were allowed to move through signatory countries in search of employment, without any further entitlements. The idea here was to rebalance the global labor market while relieving host societies of unwanted responsibilities towards refugees. Like much internationalist policy of the interwar era, the Nansen passport reflected an assumption that the problem with statelessness – and with displacement and refugeedom more generally – was essentially one of a potentially dangerous labor surplus. The solution, therefore, was not the political solution of citizenship or nationality but the practical solution of labor mobility. Enabling labor migration would simultaneously relieve host countries from the economic issues caused by “overpopulation” (a bête noire of mid-century demographers and economists) and allow displaced people to rebuild their lives on the basis of at-will employment in a global free market.

The Nansen passport came in for considerable criticism at the time – not least from Nansen himself, who saw it as little more than a stopgap solution in the absence of Western European and American unwillingness to accept refugees as citizens. Beyond that, its correlation of state belonging with access to employment and control of labor markets – far superseding the importance of any kind of access to civil and political rights – reflected a growing trend: both states and international organizations increasingly regarded stateless people as workers, with the capacity to build or disrupt a global capitalism characterized by globally enforced limits on workers’ power.

The Nansen passport’s correlation of state belonging with access to employment and control of labor markets – far superseding the importance of any kind of access to civil and political rights – reflected a growing trend: both states and international organizations increasingly regarded stateless people as as workers, with the capacity to build or disrupt a global capitalism characterized by globally enforced limits on workers’ power.

Like earlier Ottoman officials, interwar internationalists dealing with Middle Eastern refugees viewed statelessness and nationality as essentially separate issues: the first was a matter of labor, the second a largely domestic question of rights and responsibilities. For some of the luckier stateless individuals in possession of a Nansen passport, access – however limited, unprotected, and unregulated – to a global labor market did enable a kind of back-channel access to permanent resettlement, particularly in the United States and Canada, where many Armenians eventually settled and found ways to make their residency enduring. But many others were left by the wayside, an unsurprising outcome given that the Nansen passport was essentially designed to solve the labor problems of the countries hosting the stateless rather than those of the stateless themselves.

Statelessness, Nationality, Ethnicity: Palestine/Israel, 1948

Two well-known instances of statelessness unfolded simultaneously in the post-1945 Middle East: the exile of some three quarters of a million Palestinians in the 1948 war that created the new state of Israel, and the subsequent international decision to enforce Israeli citizenship as a solution to the ongoing European problem of unwanted Jewish “Displaced Persons” still languishing in Allied internment camps from Austria to Algeria. Here, we see two different stories about the relationship between statelessness and citizenship unfold. For one, the provision of a new nationality utterly failed to dislodge the recipients’ claims to their previous one. For the other, external interests declared the provision of a particular nationality to be a solution to statelessness, sometimes overriding the wishes of the stateless people themselves.

During the 1948 war for Palestine, in an effort both to secure territory and to ensure Jewish demographic dominance in the new state of Israel, Zionist military forces expelled a majority of the Arab inhabitants of mandatory Palestine into the surrounding Arab countries. To bolster their demographic claim to their newly acquired territory, the Israeli military administration immediately spearheaded a campaign for mass Jewish immigration into the Israeli state. Many European Jewish survivors of the Holocaust were still, years after the Second World War, imprisoned in “Displaced Persons” camps across Europe and European-held territory as the Allied powers, ever unwilling to open their own doors, debated various alternative solutions. The sudden military triumph of the Zionist armies in Palestine and their demographic remaking of Palestinian territory thus created a new “solution” – not to the problem of refugee statelessness, but to the problem of European and American unwillingness to allow mass Jewish immigration into their own states.

Daniel Cohen’s book In War’s Wake: Europe’s Displaced Persons in the Postwar Order explores the fraught history of this moment.

Many Jewish refugees, despite intensive Zionist recruitment efforts in the camps, expressed a preference to emigrate to the United States. But the International Refugee Office, founded in 1947 at the brand-new United Nations to deal with the impressive numbers of postwar displaced persons, saw opportunity in Israel’s eagerness to invite Jewish refugees en masse. As historian Daniel Cohen has written, “the mass emigration of Jewish refugees to Israel after 1948 was facilitated and financed by the postwar refugee regime”2– in the main, without reference to the wishes of the refugees themselves.

Displaced Palestinians, too, faced a disconnect between a new citizenship on offer and a desired political outcome on the part of their host nation. Shortly after the 1948 war, Jordan became the first – and still the only – Arab country explicitly to offer citizenship to Palestinians. The offer of Jordanian citizenship came about not as a result of refugee-led efforts, but rather because the Jordanian government was seeking to grow its workforce and demographic strength. For their part, exiled Palestinians in Arab states generally declined to advocate for local citizenship, which they feared would denude them of their claims to their lost property as well as to Palestinian nationality. Though many Palestinians did eventually accept Jordanian citizenship – some sixty percent of Jordan’s population today have Palestinian origins – it did not, in the minds of those newly minted citizens, solve the problem of Palestinian statelessness. Indeed, it did not even fully resolve the problem of residency – as was clearly seen in the early and mid-2000s when the Jordanian government stripped nearly three thousand Palestinians of their Jordanian citizenship, ostensibly in order to protect their right eventually to return to the occupied Palestinian territories.

In the case of 1948 Palestine/Israel, then, new Jordanian and Israeli citizenships stood as solutions primarily for the problems of host nations rather than stateless people. These new citizenships represented a solution to the problem of American reluctance to admit Jewish refugees, the problem of a fledgling Jewish nation-state with a dearth of Jewish citizens, and the problem of a regionally ambitious but impoverished and underpopulated Jordanian regime. But these citizenships were unresponsive as solutions to the problem of displaced European Jews who wished to start a new life in the US, or to the problem of displaced Palestinians wishing to return home.

Statelessness and the Forcible Provision of Citizenship: Bidun in Kuwait

Finally, let’s turn to an instance in which a ruling power deployed the provision of citizenship explicitly to disempower and dispossess a stateless demographic group. Kuwait, long a dependency of the British empire, became independent in 1961, at which time the new government selectively encouraged formal citizen registration. This carefully designed registration program had the fully intended consequence of leaving out approximately a third of the population, most of whom belonged to nomadic tribes in the region. Those omitted from the registration process were subsequently given the legal designation bidun jinsiyya – without nationality – and categorized as illegal residents, despite their longstanding ties to the territory now encompassed as Kuwait and their lack of citizenship elsewhere.

The bidun demographic grew further in the 1960s and 1970s, when dispossessed or displaced individuals in the surrounding Arab states were recruited into the Kuwaiti armed forces, constituting some eighty percent of Kuwait’s military by the first Gulf war in 1991. The Kuwaiti government declined to naturalize these people, thereby adding them to the pool of bidun, and increasingly viewed them as a security threat – especially with the upheavals of the Iranian revolution in 1979 and the subsequent Iran-Iraq war that dominated regional politics for most of the 1980s. In 1986, the Kuwaiti government – which had previously mostly left the bidun in place, though subject to diminished civil and political rights – began to amplify and formalize their treatment of bidun as illegal residents, stripping them of access to employment, education, housing, and health care. A number of bidun were formally expelled from the country, arousing vocal protest from the international community and various human rights organizations.

It was at this point that the idea arose of forcibly bestowing an alternative citizenship on the bidun, both as a way of ensuring their inability to naturalize in Kuwait and as a way to allow for their deportation. As a first step, the government began encouraging bidun to purchase falsified foreign passports, which enabled officials to deny those individuals whatever limited protections they had previously enjoyed from the Kuwaiti state. In 2014, the government put in place measures to buy citizenship for the bidun from Comoros, a tiny, impoverished island nation lying between Mozambique and Madagascar. Under this scheme, which mimicked a similar plan undertaken by the United Arab Emirates a few years earlier, bidun would lose all claims to Kuwaiti nationality and services, and could instead apply for visas as foreign workers in Kuwait. This plot was in time extended to include some bidun of non-Arab origin, people born stateless as the children of foreign workers in Kuwait who had no claims to citizenship elsewhere.

In Kuwait’s treatment of its bidun, we see the clearest case yet of citizenship as a solution to the problems of host nations with a fully explicit intention to dispossess and disempower stateless communities.

Here, we see the clearest case yet of citizenship as a solution to the problems of host nations with a fully explicit intention to dispossess and disempower stateless communities who were nevertheless fully connected to Kuwaiti territory. The sale of Comoros passports to bidun in Kuwait solves the problem of a Kuwaiti government wishing to deny its own nationals, as well as stateless residents of non-Kuwaiti origins, the claims of citizenship. It also serves the interests of a desperately poor country – the Comoros – for whom the sale of passports represents one of vanishingly few sources of income. For the stateless themselves, on the other hand, such a solution serves only to strip them of their few remaining sources of political protection and ensure the permanence of their social, economic, and political precarity.

In historical terms, then, citizenship has rarely operated as a straightforward “solution” to the “problem” of statelessness. Rather, the two have represented conjoined positions in the gradual remaking of the political landscape of the globe from a world of empires to a world of nation-states.

Across the twentieth century Middle East, from the Ottoman sphere to the contemporary state of Kuwait, the provision of citizenship has been just one of many possible reactions to the presence of statelessness, and not necessarily the most effective or meaningful. Indeed, where states have proffered citizenship of various stripes to the stateless, host states were seeking primarily to solve their own social or demographic problems rather than providing political rights or socioeconomic stability to the dispossessed. In other words, a historical view tells us that when citizenship has been deployed as the primary answer to statelessness – which has in fact happened less often than we might think – this strategy has most often been designed to serve the interests of states and their internationalist allies rather than the interests of stateless peoples themselves.