January 24, 2022

Ottoman Migrants, American Deportation, and the Many Paths to Statelessness

During the late 19th and early 20th century hundreds of thousands of people from the Ottoman Empire settled in the United States. Their numbers had been growing steadily each year before the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The war’s conclusion spelled the end of their former state, succeeded by the Republic of Turkey and by a number of new Arab nations under European colonial rule. It also brought a precipitous decline in immigration from the former Ottoman world. The avowed white supremacists who rewrote American immigration policy after the war ensured that migrants would face tremendous obstacles to entrance: visa quotas, increased surveillance, and a growing federal capacity to deport people. By the time of the Great Depression, migration from the former Ottoman Empire had slowed to a trickle, and many of those who came entered without a proper immigration visa.

The new Republic of Turkey managed to overturn the postwar settlements through a successful war against Greece, led by the soon-to-be Turkish president Mustafa Kemal. It became an independent state in 1923.

The old Ottoman Empire’s Arab provinces were mostly subsumed into the so-called mandate system, which involved the post-WWI British and French colonial occupation of Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Transjordan, under the supervision of the League of Nations. Theoretically, it was supposed to be a temporary state serving as a kind of training for eventual independence. In practice, it largely functioned like old-fashioned racial colonialism.

Few such migrants harbored any meaningful connections of identity with an empire that had long since dissolved and that some had left decades before. Most had been from non-Turkish ethnic groups – Armenian, Assyrian, Greek, Arab – to begin with, and some were non-Muslims whose emigration had itself been motivated by fear amidst the communal conflicts that marked the empire’s final decades. In the two decades following the war, their old and otherwise inconsequential Ottoman identities were reactivated by the American government through its growing deportation apparatus – fundamentally changing the lives of a small number of these people. Though federal deportations had been rare before the war, by the early years of the Great Depression the US government was deporting upwards of 20,000 people annually through legal channels. If they had left the Ottoman Empire as Ottoman nationals, prospective deportees remained as such in the eyes of the American government. And since the Ottoman Empire no longer existed, their deportation cases opened up a path to statelessness – a phenomenon that would burgeon over the course of the twentieth century alongside the proliferation of new states, citizenship laws, and immigration regimes.

If they had left the Ottoman Empire as Ottoman nationals, prospective deportees remained as such in the eyes of the American government. And since the Ottoman Empire no longer existed, their deportation cases opened up a path to statelessness.

With the fall of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War, each successor state created its own nationality laws largely independent of one another. Great Britain, France, and the Italian government of the Dodecanese Islands created colonial citizenships that deemed their subjects nationals of their overseas territories rather than the European nation-states that ruled them. Those who had emigrated before the 1924 Treaty of Lausanne lost their legal right to native status in their countries of origin if they missed the window to claim it, and most did. Many had no plans to return, and perhaps many others did not fully grasp that the world’s borders were suddenly hardening in the wake of decades of unprecedented mobility. Meanwhile, Turkey and Greece carried out a large-scale population exchange that redefined the status of millions of people on the basis of their confessional identity. Muslims from Greece became Turkish citizens and Greek Orthodox communities of Anatolia became Greek. While some had already become refugees, this exchange entailed a mass – compulsory – transfer of those who remained.

The Greek-Turkish population exchange, arranged through a three-way negotiation between Greece, Turkey, and the League of Nations, was formalized in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. It was the first mandatory exchange of populations, forcibly denationalizing some 1.2 million Anatolian Christians now labeled “Greeks” and about 500,000 Greek Muslims who became “Turks.”

Bruce Clark’s Twice a Stranger examines some of the short- and long-term consequences of this moment.

With the fall of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War, each successor state created its own nationality laws largely independent of one another. Great Britain, France, and the Italian government of the Dodecanese Islands created colonial citizenships that deemed their subjects nationals of their overseas territories rather than the European nation-states that ruled them. Those who had emigrated before the 1924 Treaty of Lausanne lost their legal right to native status in their countries of origin if they missed the window to claim it, and most did. Many had no plans to return, and perhaps many others did not fully grasp that the world’s borders were suddenly hardening in the wake of decades of unprecedented mobility. Meanwhile, Turkey and Greece carried out a large-scale population exchange that redefined the status of millions of people on the basis of their confessional identity. Muslims from Greece became Turkish citizens and Greek Orthodox communities of Anatolia became Greek. While some had already become refugees, this exchange entailed a mass – compulsory – transfer of those who remained.

By the 1930s, the Ottoman Empire was largely a thing of the past, but it survived in the deportation cases of people who had been born there. Though they represented a small component of the overall volume of removals from the US, the deportation cases of “Ottoman Americans” produced a disproportionate volume of diplomatic activity and correspondence due to the political upheaval involved in the dissolution of the empire. These records document the many contradictions of the new immigration regimes of the interwar period, and serve as witness to the disparate group of stateless people who fell through the cracks of the fractured empires on the new geopolitical map. Statelessness would eventually become the plight of millions of people across the world, recognized by the United Nations as a fundamental problem of our time. The history of deported Ottoman Americans reveals that even before statelessness became a problem for refugees, it had already emerged as a problem for states: modern nation-states seeking to control and define the makeup of the nation, not least through the tool of deportation.

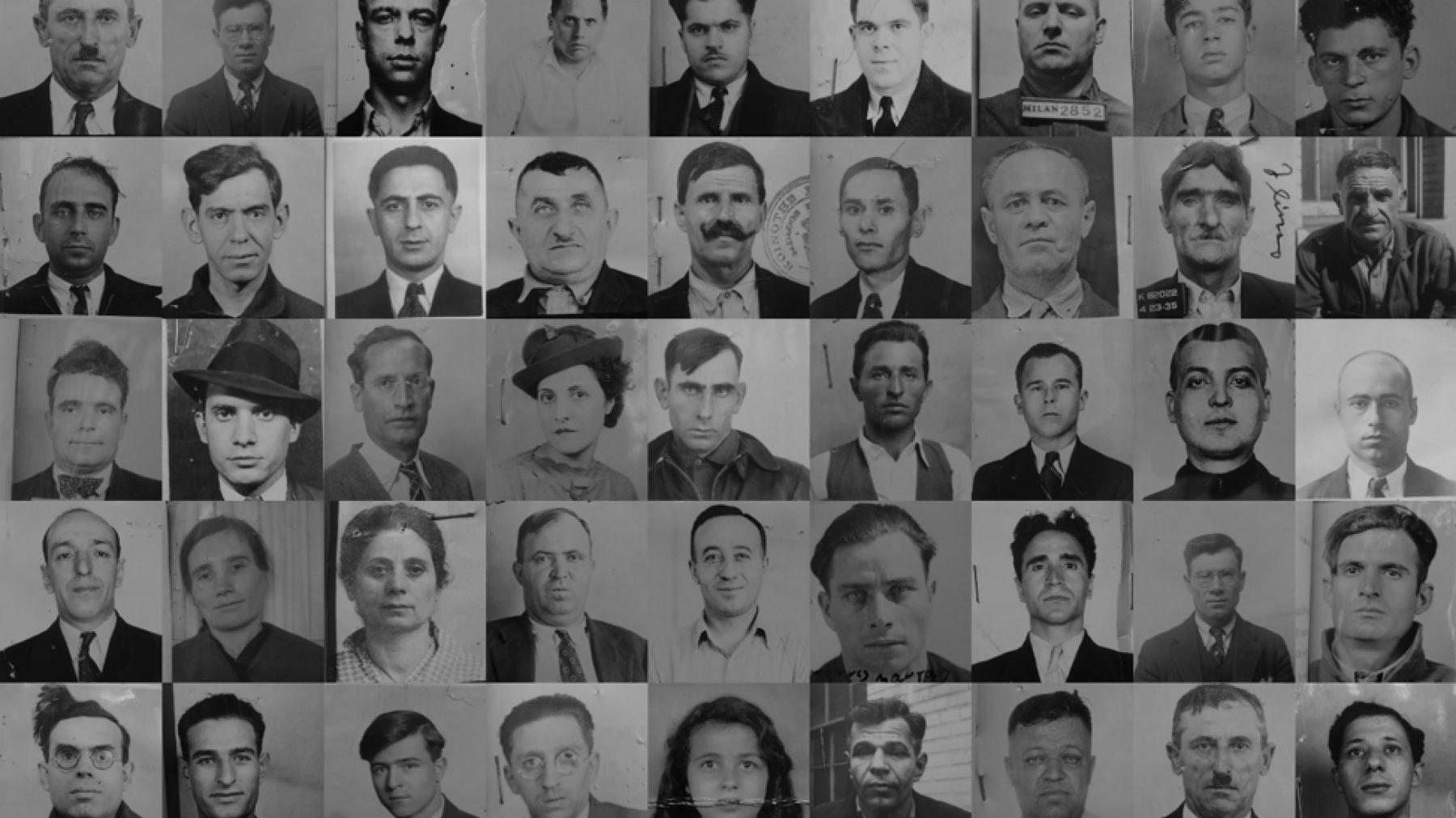

Deportation case files are a genre that few people ever encounter, but any citizen would be well served to read some. Although I was well aware that removals by Immigration and Customs Enforcement have more than doubled in my own lifetime, I did not know firsthand what goes into a deportation before accidentally encountering case files in the diplomatic records of the American archives from the 1930s. What first caught my eye was that most contain striking photographs of the individual being deported. They range in quality and context, but each one is the portrait of a person from the past, created in one of their most vulnerable moments. The files also include the transcripts of legal proceedings, which is to say interrogations by immigration officials, sometimes via interpreter. They are full of biographical details from the proceedings and other documentation, often strung together in an uncharitable manner to test whether a person deserves to remain in a country they longer have any inherent legal right to inhabit. In their invasive scrutiny of ordinary historical actors immigration files offer rich biographical detail, allowing a historian willing to read against the grain of their production to reconstruct stories of multidimensional people in the process of being erased from the official narrative of American history.

Image from case file of a a young man named Hassan from Lebanon. This case is featured in an episode of Ottoman History Podcast entitled “Syrian in Sioux Falls".

They also include documentation of the herculean efforts by law enforcement and diplomatic officials to remove such people from the United States. Deportation was a multi-step process for all, but the people in these diplomatic archives were not like all deportees. They usually lacked travel permits, passports, or any documentation attesting to their nationality. Quite often, officials could not ascertain which country should take them; if they were born in the Ottoman Empire, the place where they were born had ceased to exist as a territorial entity. The cases could stretch on for years. No two stories were the same, though consistent themes emerge. Taken as a whole, these sources reveal the paradoxical arbitrariness and senselessness resulting from the logic employed to rationalize and regulate the movement of people.

Sources on ex-Ottoman subjects deported from the United States reveal the paradoxical arbitrariness and senselessness resulting from the logic employed to rationalize and regulate the movement of people.

Like many a Greek seaman of his generation, Nick Makrinakis jumped ship in New York. He spent eight years there, roughly half of his adult life, before his arrest for having stayed on without a visa. He had broken no other laws. At the time, he had about $200 in a Greek-American bank and in his pocket a single day of wages from a construction company in Brooklyn. Back in Greece, he had a mother, wife, and two children, whom he likely supported with remittances. His own father had died at sea. Makrinakis furnished postmarked letters attesting to those relationships; as for his legal status, he had “no papers whatsoever.” At his hearing in 1936, he did not protest his deportation, only asking that he be removed swiftly and not detained long at Ellis Island.

Makrinakis would spend years in limbo because despite his testimony stating that he was Greek in both “race” and nationality, he was in fact stateless. He had moved to Greece as a teenager from the then-Ottoman island of Symi, which had recently been occupied by the Italian military. Since then, Symi had become part of Italy’s empire in the Aegean. Makrinakis was already settled in Greece when the 1924 Treaty of Lausanne that settled postwar conflicts and borders of the former Ottoman Empire went into effect. He had not laid claim to his potential Dodecanese nationality before the window closed. As far as he was concerned, he was simply Greek, like most people in the Dodecanese Islands. American immigration officials who examined his file did not initially realize he could be otherwise. However, the position of the Greek government was that his personal or communal connections to Greece were incidental, and that he was not eligible for a Greek passport, because he was not a Greek national. I found no evidence of how Makrinakis, or the American immigration officials ultimately resolved his case. A natural consequence of the stateless limbo in which he found himself was often to simply disappear from the documentary record. Perhaps in the end Makrinakis returned to Greece the same way he entered the US—illicitly. Regardless, his situation illustrates the capriciousness of the new citizenships created through the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire.

The new laws that governed migration were less about ensuring justice and more about securing power.

His was among a handful of deportation cases involving people born in the Ottoman Dodecanese pursued through diplomatic channels during the mid-1930s. In the case of Makrinakis, American diplomats did not manage to replicate their success of the prior year, during which they had deported multiple such individuals via diplomatic measures – not to Greece but to Turkey. One was John Bardelis, who had left the Dodecanese Islands with his father as a child years before the Italian occupation. His deportation to Turkey might have seemed strange, but Bardelis was content, as it allowed him early release from the state prison in Westerfield, Connecticut, where he was serving time for “carnal abuse of a female child” – his second such offense.

Turkish authorities, of course, had expressed no desire to make their country a haven for criminals from former Ottoman territories. Their issuance of a passport to Bardelis was the necessary corollary to Turkey’s denial of travel documents to people like the aforementioned Makrinakis. Since Makrinakis was Greek Orthodox, Turkey judged him to be subject to the exchange of populations, even if Greece did not. But to Turkish officials it made sense to honor the request of a passport for Bardelis, who was Catholic, and consequently not covered by the agreement in its literal reading. It is hard to imagine that any of the officials involved would have seen justice in the same laws being used to separate one family and to free a person deemed a menace to all families at the time—a perpetrator of “moral turpitude.” The new laws that governed migration were less about ensuring justice and more about securing power – in this case, over who could enter and remain in the American nation.

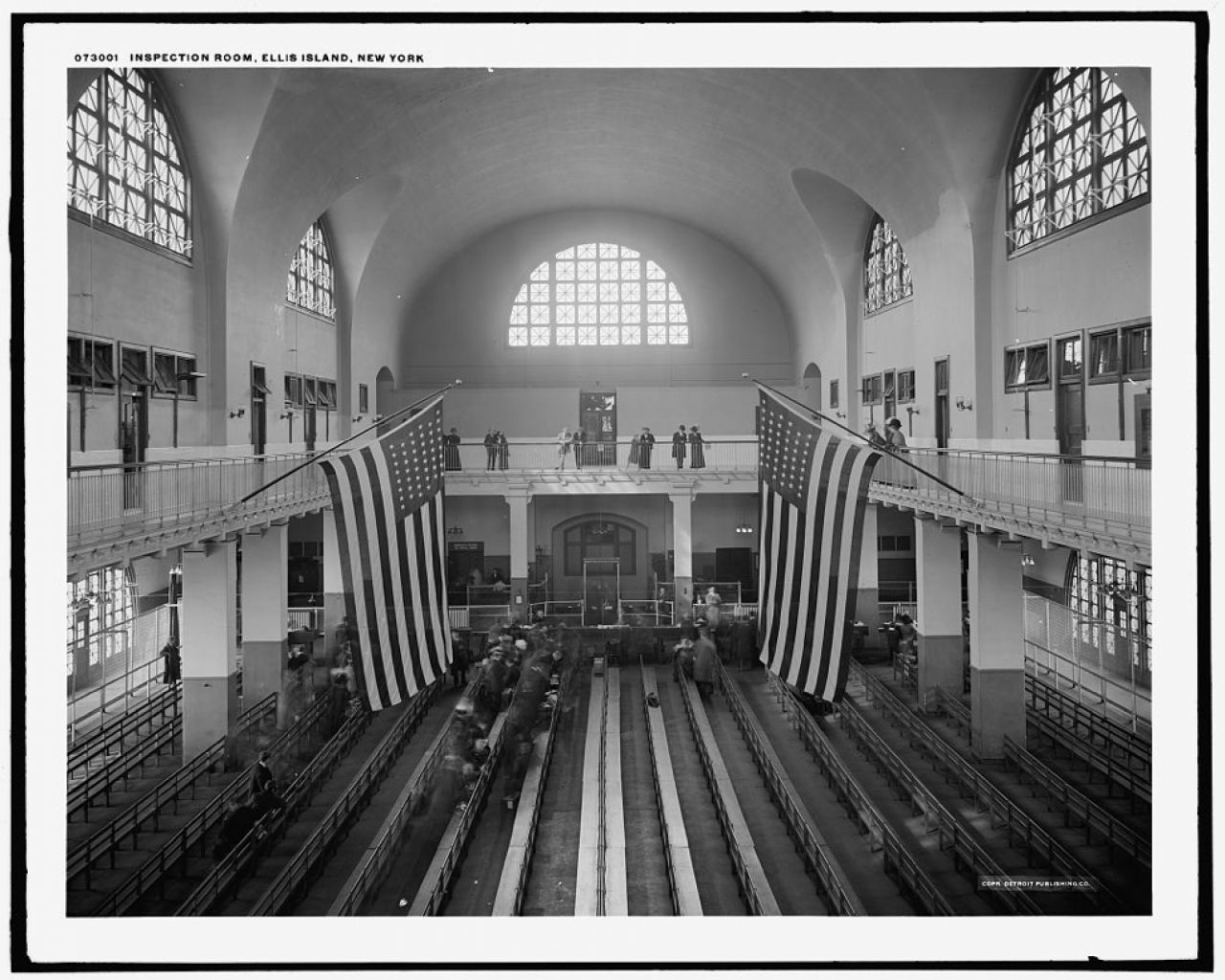

The inspection room at Ellis Island circa 1910-20. Once a major point of arrival for inspection and registration of immigrants, by the 1930s, Ellis Island’s function was largely as a center of deportation due to the creation of a visa system. Image Source: Library of Congress.

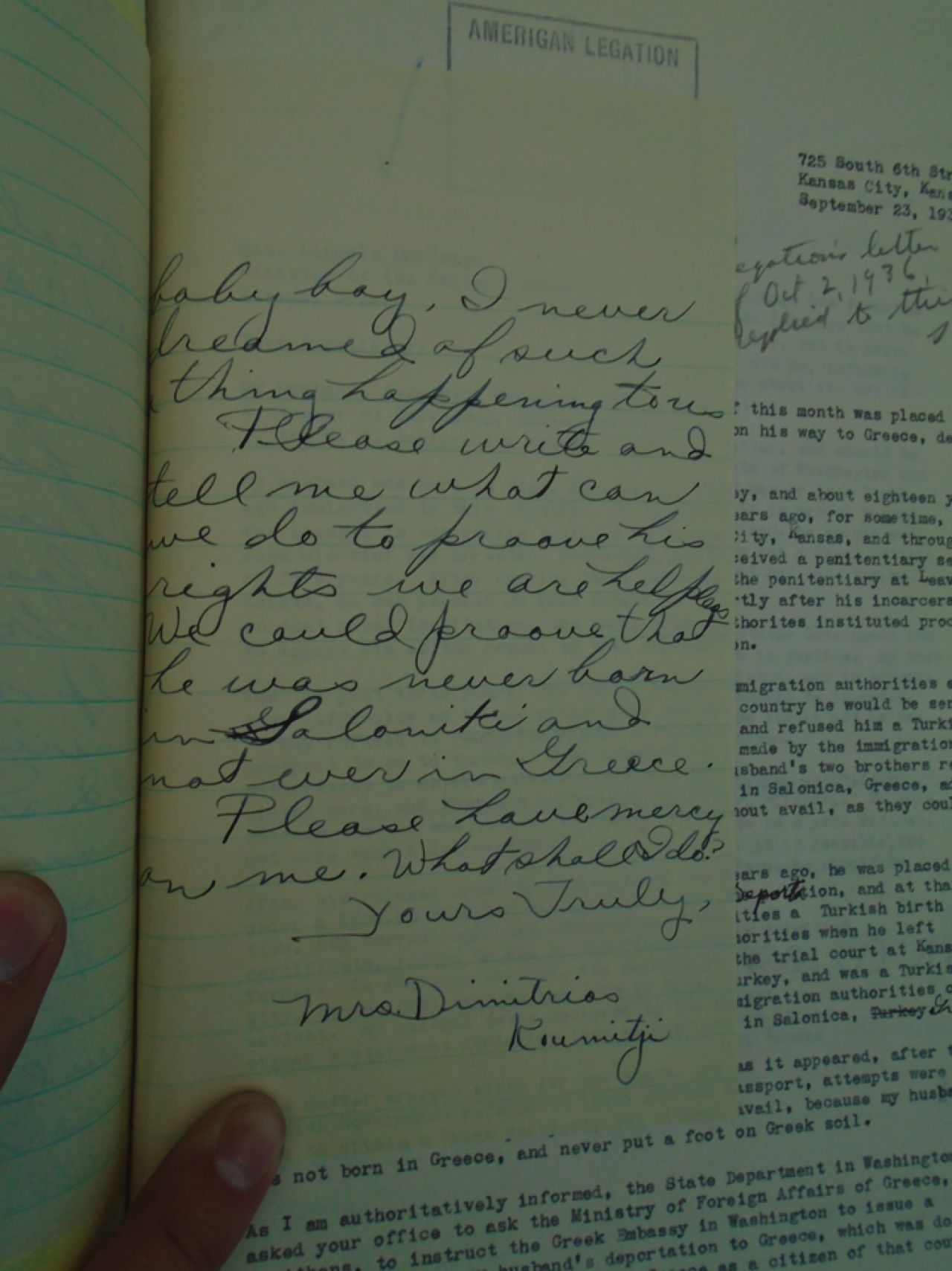

Convoluted though they were, the cases above illustrate contradictions and arbitrariness that defined the outcomes of deportation hearings for any number of people from the former Ottoman Empire. For Greeks born in what became the Republic of Turkey, deportation to Greece became a straightforward matter. They included Dimitrios Koumitji, born in Biga, not far from Gallipoli, where a successful Ottoman defense during WWI had proved pivotal to the definition of modern Turkey. Koumitji had left decades prior, setting in the US, where he served three years in prison for illegal activity at his garage business during the Great Depression. He was released early for good behavior, only to be quickly deported to Greece via steamship. His American wife, left to care for their infant child, protested. She declared that he had never been to Greece, describing the deportation as mistaken and “arbitrary” on various grounds. She also claimed that the passport issued to her husband labeled his birthplace as Thessaloniki in Greece, rather than Biga in Turkey, an outright fabrication in their eyes. US authorities informed her that the diplomatic agreements between Greece and Turkey had determined the final outcome of her husband’s deportation case. They did not directly respond to the allegation that the outcome was arbitrary.

A letter from Dimitrios Koumitji’s wife, a US citizen, protesting her husband’s deportation to Greece.

That outcome was the same for almost any Greek deportee hailing from Ottoman Anatolia. Such people included Michael Minas, who left Istanbul in 1926 and – like most Greeks resident in the former Ottoman capital – was not subject to the initial population exchanges. He had sidestepped the 1924 immigration quotas using fake documents to enter the US. Yet when finally detected, the thirty-three-year-old fireman became an unwitting latecomer to the exchange of populations due to the 1930 Treaty of Ankara, which excluded Greeks who left Turkey before 1927 from attaining the status of “established” residents. It did not matter that his father still lived in Istanbul. He was deported to Greece after a decade in the US.

For ethnic Greeks who had been born in the former Ottoman Empire and found themselves without clear citizenship status in America, the Treaty of Lausanne and Treaty of Ankara facilitated a great number of deportations that would have otherwise been impossible. Indeed, individual deportation cases occupied the bulk of diplomatic correspondence between Greece and the US during the 1930s. For former Ottoman subjects of other ethnic backgrounds, the outcomes were different: in most cases, the US could not effect a deportation of those who had missed the window to claim their new nationalities in Ottoman successor states such as Syria and Lebanon after the Treaty of Lausanne. The group most impacted was the Syrian and Lebanese diaspora in the US, which comprised hundreds of thousands of people by the 1930s. Unbeknownst to most, those who had not already naturalized in the US became stateless when they failed to claim nationality in the new French-ruled Mandate territories of Syria and Lebanon. Unlike Greece, which had a formal agreement with the new Turkish state pertaining to Ottoman nationals abroad, French Mandate authorities in Syria and Lebanon had no arrangement about these individuals. Though they were theoretically Turkish nationals, in many cases, Turkey refused to accept such people as deportees, even when documentation showed that they had come to America as Ottoman subjects. In the case of at least one man, which stretched on for years, the republican government issued a personalized decree stripping him of the Turkish nationality he had ostensibly never possessed.

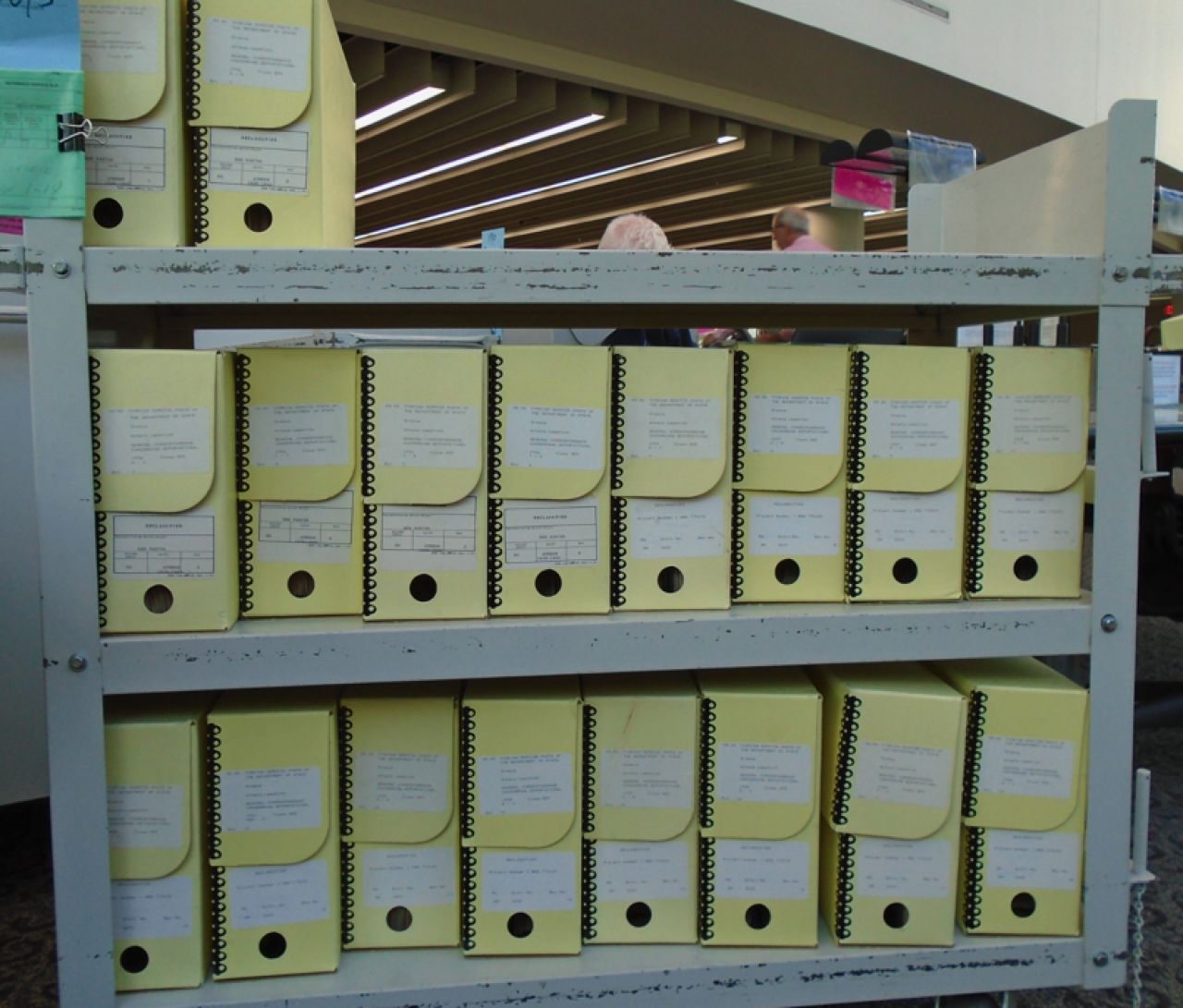

A series of archival documents encompassing diplomatic correspondence concerning hundreds of individuals who were ordered to be deported to Greece between 1936 and 1940. The number of Greek deportees during the 1930s was small in comparison with those to Mexico, Canada, and many other points of origin for American immigrants.

De facto statelessness that enabled them to remain within the US might have been a more preferable indignity than deportation for some Ottoman-born Americans. This was likely true for certain Christian demographics such as Armenians and Assyrians who lost their Ottoman nationality while living in America. I have not identified a single case from the interwar period in which Turkey issued a passport for deportation to an Armenian who had left the Ottoman Empire for the United States. Many such people appear to have lived out their lives as Americans, whatever their formal citizenship status. This includes a teenager sentenced to deportation to Turkey after briefly working at a cigar shop where illicit activities were found to occur. He was eventually able to stay in the US and start a family of his own. The same was true for a young Assyrian man from Diyarbakir, whose family in the United States had arranged for him to be smuggled into the country via Cuba. Though the outcomes were possibly favorable to such people, they also acquiesced to the political agenda of dispossessing Turkey’s non-Muslims – a process that continued long after the Armenian genocide of 1915 and the subsequent fall of the empire.

The Armenian genocide of 1915-1916 killed perhaps a million Armenians via a brutal deportation through the Syrian desert. In the early years of the Turkish republic the state continued to target Armenian property and subjects, appropriating land, pushing out remaining Armenian communities, and enforcing new forms of cultural and linguistic assimilation for those who remained. Historian Lerna Ekmekçioğlu has traced this history in her engrossing book Recovering Armenia: The Limits of Belonging in Post-Genocide Turkey.

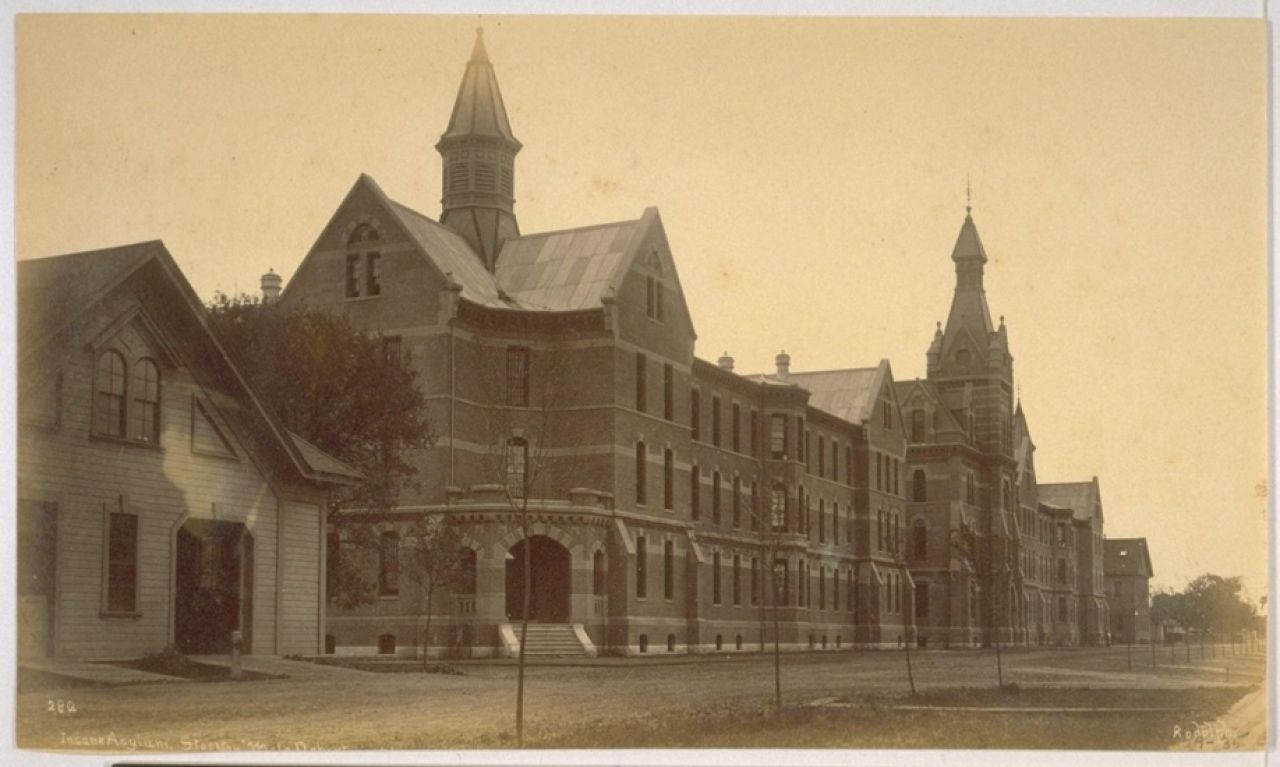

During the First World War, outcry at the plight of Armenian Christians in the Ottoman Empire had been central to the American public’s perception of the conflict. Despite that context, the American deportation apparatus had not shown much mercy towards Armenian migrants who entered its grasp. It was only the respect of the United States for Turkey’s own exclusionary practices that ironically saved them from deportation. In one case, diplomats spent years trying to secure a Turkish passport for Apraham Gedigian from the predominantly Armenian town of Hadjin, which had been subject to wholesale deportation during the genocide and mostly destroyed during the subsequent Turkish national struggle against the French occupation in Cilicia. Gedigian seems to have in fact fought alongside the French with the Armenian Legion, but his testimony was vague due to a poor command of English and psychological distress. He had not committed any crime to warrant his removal from the US; his questioning was carried out at a mental hospital, where he was institutionalized and therefore counted as a “public charge” eligible for deportation.

The men’s wing of the asylum in Stockton, CA where Gedigian was living. Asylums and hospitals were not safe spaces shielded from the roving gaze of the Immigration and Naturalization Services. They were part and parcel of its enforcement apparatus. Image source: Online Archive of California, UC-Berkeley.

Deportation represented a regressive form of biopolitics that meted out the same basic punishment to mental patients and single women as it did to felons. In official correspondence, American diplomats alluded to their grudging participation in this absurdity mostly when they believed it compromised their overall diplomatic mission. In Gedigian’s case, the American ambassador warned that further pursuit of deportation might offend Turkey, as the man in question was from a region already subject to wholesale expulsion of Armenians. “Deportation cases are the bane of our existence,” he lamented. “I fear in the case of an insane Armenian it will be next to impossible.”

In Gedigian’s case, the American ambassador warned that further pursuit of deportation might offend Turkey, as the man in question was from a region already subject to wholesale expulsion of Armenians. “Deportation cases are the bane of our existence,” he lamented. “I fear in the case of an insane Armenian it will be next to impossible.”

A consular official in Beirut offered a similar judgement in the case of a young woman named Mary, who received a deportation sentence after being caught working in a brothel. He implored the State Department to relieve him of continued pursuit of a passport for Mary from the French authorities, stating that it was not possible under the Syrian nationality laws and would only reflect poorly on his office. Mary had been improbably judged a Syrian national via a short-lived marriage to a man born to Syrian parents on a steamship bound for New York City. France would not count such a person as Syrian even if he had not naturalized in the US. Mary herself had been born in Czechoslovakia, having left the country with her parents as a child. The reason American authorities instead sought deportation to Syria via her dubiously Ottoman-born ex-husband was that under Czechoslovakian law of the time, a woman who married a foreign national lost her citizenship. Even though this practice had been made illegal within the United States, American officials had to respect the nationality laws of their counterparts in the bilateral process of a legal deportation.

The wide degree of deference shown to other nations’ nationality laws in deportation is also evidenced by the case of Tommy Georgio, who lived as an immigrant in Syracuse, NY for decades before a crackdown on the brothel run by his American wife. Georgio was born on the Greek side of the modern border with North Macedonia, when the entire region was still part of the Ottoman Empire. He left before the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 in which Greece annexed his home region. Georgio’s deportation case tested the limits of the exchange of populations: though Greeks born in modern Turkey became Greek nationals, the same right was not extended to Georgio because his hometown had become part of Greece after his departure but before the Greco-Turkish war that followed World War I. In rejecting repeated American requests for a passport for Georgio, Greek officials felt comfortable stating their unwillingness to issue a passport to someone who was not ethnically Greek: Georgio hailed from a predominantly Macedonian region that would indeed become a flashpoint in the Greek Civil War after the Second World War. Such migrants were deemed undesirable, even if they identified as belonging to Greece.

Because the letter of the law backed up the spirit of the Greek nation-state, Georgio was judged to be an Ottoman national not subject to the population exchanges and therefore deportable to Turkey. But according to the same principle applied the case of Nick Makrinakis, Turkish authorities disagreed. In such cases, statelessness was the only status all relevant parties involved agreed upon. Tommy Georgio likely agreed with this outcome. He had hired a lawyer to challenge the judgment that he was part of the brothel business and attest to his model conduct since. His deportation file produced a trove of documentation that not only revealed the intimate innerworkings of an interwar brothel in a small US city but also how ordinary, imperfect people mobilized discourses of citizenship and morality to defend their rights to remain in a society to which they belonged. Though their decisions and self-representation were shaped by the laws and norms of that society, the moments in which their resolve matched that of the resolute but dispassionate machinery they resisted are the starting point for a social history of statelessness resists replicating the logic of immigration regimes with a greater coherence than they ever possessed.

The concept of statelessness coalesced as a modern international issue, and a legal category, after the Second World War, but the origins of practices associated with it stretch back to European colonial empires of the 19th century and to countries like the US: nation-states with defined concepts of citizenship that presided over populations excluded from its privileges in part or whole. The interwar period brought a shift. The United States began to erase old forms of statelessness, granting citizenship to Native American communities in the same year that the Johnson-Reed Act established the racially-biased immigration quotas that ultimately lured many migrants into the deportation dragnet. Subjects of the British and French mandates of the Middle East became part of that story because they were granted a local nationality, making it clear that they were not meant to become British and French nationals. When they sidestepped the oppressive immigration visa system to join family and broader members of their diaspora communities in the United States, their subsequent deportation was facilitated by the new nationality laws.

During the interwar period, there was significant overlap between the emergent concept of a stateless person and the refugee in the international arena, but most of the stateless people from the Ottoman Empire that emerged out American deportation cases were not refugees in any meaningful sense. Their stateless status was laid bare only through American efforts to expel them. In this regard, their statelessness was an inherent problem to US immigration authorities, but not necessarily to them. Statelessness could even be conceived as having been empowering in some cases. I have found at least one case of an incarcerated Lebanese immigrant refusing an offer to obtain nationality from the French Mandate authorities in order to avoid deportation. Likewise, being stateless did not enable Ottoman Armenians in the US to return to their ancestral villages in what had become the Republic of Turkey, but it did help them evade what in some cases would have been a second deportation. The Armenian refugees who became nationals of Syria and Lebanon enjoyed certain rights; but the nationality they obtained did not automatically help them go elsewhere, nor did it offer a path to return.

“Stateless” is a label that can describe very different populations coming from a wide variety of political circumstances. It has never inherently signified the deprivation of a specific national status that some particular individual actually wanted; indeed, whether or not statelessness was advantageous or problematic for a particular prospective deportee depended on circumstances and aims. Still, these individual, idiosyncratic, varied paths to statelessness throughout the past century may obscure the element that each case of statelessness shares: the virtually inalienable right of a state to deny a person entry to the country of their birth. This right, possessed by all states within the interwar international order of the League of Nations, supersedes another country’s desire to deport. The two might be reconciled through diplomacy, but the cases of Ottoman-born deportees show that American authorities relented when prospective receiving countries enforced the letters of their law.

These individual, idiosyncratic, varied paths to statelessness throughout the past century may obscure the element that each case of statelessness shares: the virtually inalienable right of a state to deny a person entry to the country of their birth.

To this day, international law has proven unable to consistently protect the right to nationality enshrined in the UN Declaration on Human Rights when states claim their rights to deprive it. But in a world of highly uneven citizenship rights and access to mobility across different nationalities, the mere fact of having a nationality of some kind is not always very empowering. This does not mean that statelessness does not in some sense represent an inherent violation of one’s human rights. Rather, the problems that statelessness posed for the American deportation state during the interwar period should prompt us to ask questions about the origins of the UN’s mandate to end statelessness. Given that refugees and asylum seekers are frequently disaggregated from stateless people, implicitly freeing host countries from the obligations to extend the entitlements of citizenship, the eradication of statelessness may serve the interests of its members and their domestic migration regimes as much as it restores the rights of the growing number of people who fall under that label. And the histories of deportation offered above warn that governments looking to exclude will seek and often succeed to use whatever protocols exist toward those ends, regardless of the spirit of the laws and international agreements concerning migration to which they themselves are signatories.

List of reading

Gratien, Chris, and Emily K. Pope-Obeda. 2018. "Ottoman Migrants, U.S. Deportation Law, and Statelessness during the Interwar Era". Mashriq & Mahjar. Vol. 5, no. 2.

Gratien, Chris, and Emily K. Pope-Obeda. 2020. "The Second Exchange: Ottoman Greeks and the American Deportation State during the 1930s". Journal of Migration History. Vol. 6, no. 1: 104-128.

Gratien, Chris, and Sam Negri. “Narrating Sephardic Histories: A Reflection” in Aguirre-Mandujano, Oscar and Tinaz, Kerem. Sephardic Trajectories. University of Chicago Press, 2021, 157-173.

See the ongoing Deporting Ottoman Americans series for more https://www.ottomanhistorypodcast.com/p/doa.html

Balgamis, A. Deniz, and Kemal H. Karpat. Turkish Migration to the United States: From Ottoman Times to the Present. Center for Turkish Studies at the University of Wisconsin, 2008.

Barkan, Elliott Robert. Immigrants in American History: Arrival, Adaptation, and Integration. ABC-CLIO, 2013.

De Genova, Nicholas, and Nathalie Mae Peutz. The Deportation Regime: Sovereignty, Space, and the Freedom of Movement. Duke University Press, 2010.

Demirözü, Damla. "The Greek-Turkish Rapprochement of 1930 and the Repercussions of the Ankara Convention in Turkey." Journal of Islamic Studies 19, no. 3 (2008).

Fahrenthold, Stacy. “Claimed by Turkey as subjects: Ottoman Migrants, Foreign Passports, and Syrian Nationality in the Americas, 1915-1925” in Can, Lâle, Michael Christopher Low, Kent F. Schull, and Robert W. Zens. The Subjects of Ottoman International Law. Indiana University Press, 2020.

Gatrell, Peter. The Making of the Modern Refugee. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Gualtieri, Sarah. Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Gutman, David E. The Politics of Armenian Migration to North America, 1885-1915: Sojourners, Smugglers and Dubious Citizens. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

Hester, Torrie. Deportation: The Origins of U.S. Policy. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

Kanstroom, Dan. Deportation Nation: Outsiders in American History. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Khater, Akram. Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870-1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Luibhéid, Eithne. Entry Denied: Controlling Sexuality at the Border. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Mays, Devi. Forging Ties, Forging Passports: Migration and the Modern Sephardi Diaspora. Stanford University Press, 2020.

Moloney, Deirdre M. National Insecurities: Immigrants and U.S. Deportation Policy Since 1882. Univ Of North Carolina Pr, 2016.

Naar, Devin E. 2007. "From the "Jerusalem of the Balkans" to the Goldene Medina: Jewish Immigration from Salonika to the United States". American Jewish History. 93, no. 4: 435-473.

Nail, Thomas. The Figure of the Migrant. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015.

Ngai, Mae M. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton University Press, 2004.

Pope-Obeda, Emily. 2019. "Expelling the Foreign-Born Menace: Immigrant Dissent, the Early Deportation State, and the First American Red Scare". The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 18, no. 1: 32-55.

Pope-Obeda, Emily. "When in Doubt, Deport!": U.S. Deportation and the Local Policing of Global Migration During the 1920s (Ph.D. Thesis). University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, 2016.

Siegelberg, Mira L. Statelessness: A Modern History. Harvard University Press, 2020.

Stein, Sarah Abrevaya. Extraterritorial Dreams: European Citizenship, Sephardi Jews, and the Ottoman Twentieth Century. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Torpey, John. The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Zolberg, Aristide R. A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America. 2008.