January 24, 2022

The Status of Bengalis in Assam: From Migrant to Refugee to Stateless

In the earthshattering events of 1947 we collectively call “Partition,” the ‘united Indian territory’ was not vivisected uniformly: Punjab and Bengal bore the main burden of division and suffered much of the worst violence. But the final verdict of the Radcliffe Line touched other spaces as well, some of which had their own pre-partition history of migration and settlement. The province of Assam, long a site of close interchange with its neighbour Bengal, found itself after partition struggling to redefine this longstanding relationship of migration and exchange in a new political context of separate and oppositional nation-states. It was a process that turned Bengalis in Assam from migrants to refugees to, eventually, stateless persons with no path to belonging in a contemporary Indian body politic.

The case of Bengali refugees in Assam is particularly interesting because during and after partition Assam received migrations from both sides of the Hindu/Muslim divide. On the one hand, it became a place of refuge for Hindu Bengalis leaving the part of Sylhet that had been severed from Assam during partition. On the other, it eventually saw considerable numbers of Muslim Bengalis who had fled during partition returning to their former homes, now as refugees. The question of refugee rights in Assam, then, crossed over the communal lines drawn during Partition and suggested a different kind of post-partition landscape of citizenship – one that devised locally specific tests of indigeneity as a way of excluding more recent arrivals, both Muslim and Hindu. This is a case, in other words, where a longstanding and complex history of migration and settlement across religious and linguistic communities gave way to a distinctly hostile native/migrant divide set in a new era of national politics. Post-partition Assam thus produced a new form of statelessness: one marked not by communal affiliation but by an experience of migration that would in an earlier era have been completely unexceptional.

In Assam, a longstanding history of migration and settlement across religious and linguistic communities gave way to a distinctly hostile native/migrant divide set in a new era of national politics. Post-partition Assam produced a new form of statelessness: one marked not by communal affiliation but by an experience of migration that would in an earlier era have been completely unexceptional.

Colonial Assam: Migration

Mentioned in ancient epics like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, the state of Assam was located at the crossroads of traditional migration routes. Ancient chronicles of the Ahom kings (1228-1826) indicate that because of this geographical position Assam was long a space characterized by all sorts of migration. In 1826 Assam came under British colonial rule and became a part of the Bengal Presidency, a region with whose eastern regions it had long had a kind of inter-dependence via the river and trade routes that connected Assam and Bengal with the western Gangetic basin. The idea and formation of a composite population was therefore built into the culture of this land.

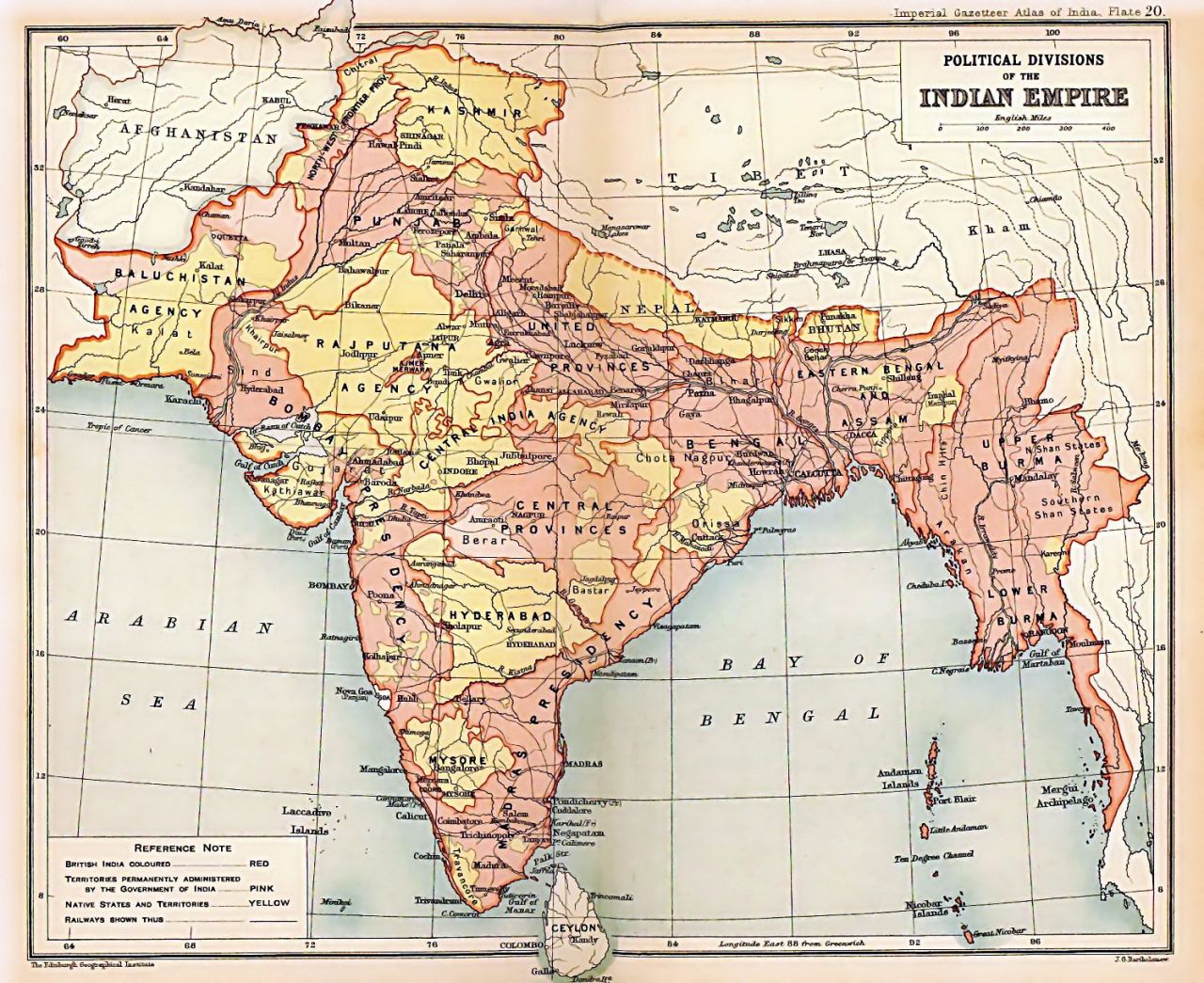

Map of the British Indian Empire in 1909 during the partition of Bengal (1905–1911). British India appears in pink and coral. Assam Province (initially Province of Eastern Bengal and Assam) can be seen towards the north-eastern side of India. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The economics of colonial rule now added further layers to these existing patterns of exchange and migration. Assam became a region for the investment of capital on cash crops like tea, for experiments with migrant labor, and the for the active settlement of communities to serve the practical need of colonial rulers. The British government encouraged migrant tea labourers and brought in seasonal Muslim migrants to work the land. At the same time, settled agricultural labourers, both Muslim and non-Muslim, began feeling threatened by the monopoly of English-educated Hindu Bengali professional classes – also introduced by the British to serve as upper and lower division clerks for the British civil administration. A non-agrarian tribal population contributed further to the complexity of the demographic situation. Already, then, we can see the ways that colonial demands and practices were contributing to new tensions – linguistic, communal, and class-related – among migrants, settlers, and native populations across the newly incorporated province of Assam.

This colonial strategy had parallels with other British efforts to create political and sometimes spatial segregation between Hindu and Muslim communities across the subcontinent, constructing (for instance) separate voting franchises along communal lines from 1905 onwards. Many scholars have pointed out the colonial origins of the Hindu/Muslim political divide in Raj-era India; the strategy described here to divide migrants from indigenous populations was similar.

In the so-called Partition of Bengal in 1905, the Raj (the British administration in India) created a new province called “Eastern Bengal and Assam.” Under this plan, Muslim peasants from Eastern Bengal started settling down permanently in Assam. Desperate to occupy a piece of land in Assam, which was sparsely populated compared with East Bengal, the Bengali Muslim peasant class moved so quickly to occupy cultivable land and buy property that the British administration introduced a ‘Line System’ in 1920 designed to segregate immigrants from natives. It tried to implement rules of not exchanging pattas of lands between locals and immigrants. Partly as a consequence, Assam became a segregated space; the population in the Brahmaputra valley consisted of Assamese ‘son of the soil’, whereas the other part of Assam, the Surma/Barak valley, consisted mainly of Bengalis. Notably, both spaces were religiously mixed; the lines of division in Assam were migrant/settler, not Hindu/Muslim.

In 1947, because of this long history of contested migration and settlement, Sylhet became the only region of British India to hold a referendum over its national fate; Indian political leaders unanimously agreed that the Bengali-speaking district in Assam could decide through a plebiscite whether it would form a part of Pakistan or not. The referendum’s outcome separated Sylhet from Assam for the first time since 1826, attaching the Hindu majority districts to Assam. The remaining southern parts of Assam consisted of three Bengali-speaking districts, where partition now set Assamese and immigrants against each other. For the Hindu Bengalis of Sylhet, ‘doubly punished’ as they witnessed Sylhet ‘cut into pieces,’ it was the ‘last betrayal.’ This development now produced a new migration of both Hindu refugees and Muslim returnees from Sylhet and the rest of East Bengal, creating new kinds of refugeedom and statelessness across the newly constituted border separating India from Pakistan.

Partition-Era Assam: Refugeedom

Prior to partition, Hindus and Muslims of Bengali descent had accounted for more than 40 per cent of the population of Assam. Three major migrant groups from East Bengal were already prominent in the society, economy and politics of Assam: Muslim cultivators from Mymensingh, whom the Assamese called Mymensinghias; the social elites, recruited by the British administration from various districts of East Bengal to serve in the white-collar job sector; and the char dwellers, a Muslim diasporic community settled permanently in the sandbanks of the Brahmaputra. All of them were collectively seen as immigrants and as non-indigenous people, competing for already-scarce resources in Assam. As partition gave birth to new communities of people called ‘refugees,’ the state’s government’s perspective was that since Assam was already overburdened with the existing immigrants, its local communities should not have to take in further waves of Partition-displaced refugees from East Bengal.

Thousands of refugee families, most with some contact in Assam, nevertheless crossed the border on foot, mostly without formally registering themselves as ‘refugees.’ Since the State government was largely hostile to them, their intention was to purchase a piece of land or a tiny piece of property, by any means, with the small amount of money they were carrying. Surabhi, an Assamese monthly paper published from Brahmaputra valley, strongly demanded Government action vis-à-vis the refugees. Some cultural organizations like the Asom Jatiya Mahasabha, ideologically committed to an Assamese national vision, requested the government to refuse to issue Domicile Certificates to migrants, so that they would not be able to apply for citizenship in future.

This section of the Kushiyara River flows through Assam, along the newly-constituted border between India and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The narrow river allowed for easy crossing, facilitating silent migration into Assam.

And further, since Sylhet (as we have seen, formerly part of Assam) had become part of Pakistan, Hindu Bengalis also began to pour into Assam as refugees. Worsening the situation, all food distribution routes in the hills were blocked; central aid was minimal; and the State government tried to stop refugees from settling on surplus land or in tea gardens. The Central Government based in Delhi, in opposition to the State government’s interest, tried to assess the availability of grazing reserves, fallow cultivable lands and other viable options by organizing a committee. By the late 1950s this post-Partition refugee influx had created a situation of famine in Assam, and the tense but manageable relations between Assamese locals and Bengali immigrants during the colonial period had moved into an era of violent local attacks on the Bengali refugees.

By the late 1950s this post-Partition refugee influx had created a situation of famine in Assam, and the tense but manageable relations between Assamese locals and Bengali immigrants during the colonial period had moved into an era of violent local attacks on the Bengali refugees.

In 1950 this development produced the Nehru-Liaquat Ali Khan Agreement, also known as the Delhi Pact: an agreement intended to create conditions in both countries where the “minorities” could feel secure and prevent their migration to the other country. Indeed, its architects hoped to encourage those who had migrated to India or Pakistan after Partition to go back to their respective places of origin. Thus, after the Delhi Pact, large groups of Bengali Muslim immigrants who had migrated to East Pakistan after Partition began to return and claim their old settlements in Assam. With this new wave of migrants, both Hindu refugees and Muslim returnees, the situation began to spiral out of control. The Assam government continued to oppose providing shelter or distributing land to the refugees, against the expressed attitude and policies of the Government of India. The lands where some of the refugee families received allotments were not suitable either for cultivation or for resettlement. The Centre formed a Committee of Enquiry under Sri Prakasa, the-then Governor of Assam. He echoed the same voices, reporting on the uninhabitable condition of the lands.

Tensions rose rapidly between Assam and the central state. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the-then Home Minister of India warned, ‘I am afraid, your letter betrays lack of a sense of urgency in settling the refugee problem’ and he cautioned, ‘Everywhere, wherever we have to deal with the refugee problem, we had to give priorities even against local sentiments’. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru wrote to Gopinath Bordoloi, then Chief Minister of Assam, that ‘Assam was getting a bad name for its narrow approach to this problem’ and threatening that ‘if Assam adopts an attitude of incapability to solve the refugee problem, then the claims of Assam for financial help (would) obviously suffer.’ Assam – now becoming a space for refugees from both sides of the partition lines – was at odds not only with its new inhabitants but also with its own new central government over how to respond to the massive numbers of migrants, both Muslim and Hindu, now vying for land within its borders.

Border area between Assam and Bengal.

Post-Partition Assam: Statelessness

It was under these tense conditions that refugeedom became statelessness for some of the displaced. During the early 1950s, the Immigrants (Expulsion from) Assam Act, the Administration of Evacuee Property Act, the Evacuee Interest (Separation) Act, and the Influx from Pakistan Control Act all served to restrict immigration and permanent settlement of Bengalis in Assam. In particular, the State government was busy designing methods to keep the explicit difference between indigenous and non-Assamese people and to regulate the acquisition of land by outsiders., even as large numbers of refugees were residing in railway colonies with railway employees where they could sometimes pick up jobs. Until and unless the refugees produced their own food and developed their resources, the policymakers declared, they would remain a burden on the Province.

Assam was now wracked with Bengali-Assamese conflict. A conspiracy theory stated that Bengali cultural expansionists were spearheading a persecution of Assamese language and culture. The inequitable competition for white-collar jobs and other employment in the colonial offices where Bengalis were preferred – even after Partition, the Bengali babus dominated much of the job sector – compounded an Assamese sense of grievance. Many Assamese feared that the demographic shift would not only increase Bengalis cultural hegemony but might eventually result in a total transfer of political power to Bengalis in Assam. Assamese elites became increasingly resentful about a supposed Bengali predominance over the Assamese in every field. Myron Weiner depicted Assamese insecurity in his book Sons of the Soil: Migration and Ethnic Conflict in India: ‘The Assamese found the Bengali in a superior and himself in a subordinate position. The teacher is a Bengali, the pupil Assamese. The doctor is a Bengali, the patient Assamese. The pleader is Bengali, the client Assamese. The shopkeeper is Bengali, the customer Assamese. The Government official is Bengali, the petitioner Assamese’. Thus, Assamese nationalist thinkers kept on urging people to take measures for the protection of their linguistic identity and for the adaptation of Assamese language as a criterion for Assamese nationality. This strife led the Assamese middle-class to organize socio-political movements for an adequate share of employment in the services sector, as much as the restoration of their ethnic culture and identity. A process of literary regeneration took shape and produced strong notions of cultural nationalism. Assamese elites found the Bengali refugees to be an obstacle in the path of their intellectual growth. Disputes over languages ushered in a crisis of linguistic identities that became a theme of the politicization of regionalism and politics over the Bengali refugees.

Contemporary mural in Silchar Station, Assam, commemorating Bengali language martyrs who died on 19 May, 1961, when Assam police opened fire on unarmed protesters demonstrating against laws making Assamese the only official language of Assam.

The greater worry of the Assamese Hindu communities, though, was demographic; for the census of 1951 indicated that because of the return of Muslim Bengalis, a decisive shift had taken place. Upon return, these communities declared themselves linguistically Assamese, telling census officers “amago bhasa osomia” (our mother tongue is Assamese) – itself a Bengali sentence – to legitimize their repossession of lands and houses they had left behind when they had migrated to East Pakistan. From 1951, Bengali Muslims succeeded in registering them as Assamese in the census – a development that served to heighten tensions over their position in a postcolonial Assam.

The precarity of their position, though, was reflected in the language, both official and unofficial, used to describe their political status. Though the term ‘refugee’ had found a legal mention in the Partition Proceedings in 1947, the Government of India tried hard not to categorize those displaced by partition as refugees, since the use of this term would require the state to provide social security and other forms of assistance. Instead, they were termed ‘displaced persons’, ‘migrants’ or ‘evacuees’, reflecting the dilemma of the state making concrete policy decisions around them. From the early 1950s, the authorities started referring to them as ‘optees’ and ‘migrants’. From the late 1950s, the term to denote a refugee moved toward ‘evacuees’ and ‘illegal aliens or migrants’.

At the ground level, too, the terms denoting refugees changed according to circumstance. For example, the post-Partition Bengali refugees were initially referred to as bhogonia, which denotes ‘someone who was forced to flee from their place of origin’ in the Assamese language. From the early 1950s, though, as the immigrant Bengalis started acquiring land and capturing more white-collar jobs in Assam, they were termed bongals or bongali: deliberately referencing derogatory modes of describing tribal communities unwilling to adopt Assamese habits and manners. The term bhogonia soon changed to bohiragato – ‘outsider’ – as Bengali settlers morphed into both an economic threat and a political challenge to the Assamese. When the refugees started emerging as a potential voting franchise, still another word for them began to appear: bideshi, or ‘foreigners’ who hailed from Bongal Desh. After a riot in 1964, the refugees were derogatorily cast as ‘infiltrators’, ‘Pakistani minorities’ and ‘fugitives’. During the Liberation War of 1971, the popular word became sharanarthi – someone seeking refuge and protection – in official records and reports.

Bengali refugees were initially referred to as bhogonia, ‘someone forced to flee from their place of origin.’ But from the early 1950s, as the immigrant Bengalis started acquiring land and capturing more white-collar jobs in Assam, they were termed bongals or bongali: deliberately referencing derogatory modes of describing tribal communities unwilling to adopt Assamese habits and manners. The term bhogonia soon changed to bohiragato – ‘outsider’ – as Bengali settlers morphed into both an economic threat and a political challenge to the Assamese. When the refugees started emerging as a potential voting franchise, still another word for them began to appear: bideshi, or ‘foreigners.’

All this eventually had political repercussions. Assamese Hindus’ fear that the Bengali Muslims would swamp them someday by the growth of the community and its increasing land ownership led them to advocate for changes in the Citizenship Act of 1955. The new stress on the category of ‘citizenship by birth’ over of ‘citizenship by registration’ made the condition of the Bengali refugee families newly vulnerable. Following the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971, a cut-off date was fixed – 25 March 1971 – for any migrant-refugees to be offered Indian citizenship.

The war followed a brutal West Pakistani government effort to eradicate Bengalis and Bengali nationalism from East Pakistan. There is a general consensus among scholars that the West Pakistani action amounted to genocidal violence again Bengalis. The war sparked yet another major refugee crisis, with as many as 10 million Bengalis fleeing into India to escape the bloodshed.

The Indira-Mujib Pact of 1972 declared that all refugees who had arrived and settled down in Assam or any other states of the eastern border by this date would be eligible for citizenship under the Citizenship Act of 1955. But henceforth, Bengali migrants who crossed the borders into Assan would be not “citizen-refugees” but stateless persons. The province, for so long marked by its migratory populations and enduring relationships with India and Bengal alike, would now preserve citizenship only for those who could claim jus soli.

Following the trauma of Partition and the creation of the new international border, India chose to deal with the refugees mainly as an administrative challenge rather than a political problem: refugees had to depend on the benevolence of the state, rather than a regime of rights. Jawaharlal Nehru – like many other leaders of the time – viewed the refugee conventions mainly as responses to the displacement in Europe, and feared the international interference and criticism that involvement with the Convention seemed likely to bring. He was also uncertain that India would be able to maintain the minimum standard of hospitality towards the refugees, and so decided to keep the issue internal. The approach of the Centre and respective state governments were therefore always essentially ad hoc. Consequently, Partition-displaced ‘legal’ refugees and other categories of asylum-seekers who had fled from their home countries due to persecution or other reasons became subject to the same rules and regulations as any other migrants: the final fate of the refugees was determined by the protections ensured by the Indian Constitution.

It proved an insufficient protection. In comparison to other north-eastern states, the anti-migrant movement in Assam took a more and more organized form, promoting the myth of gradual minoritisation of the hosts and the capture of socio-political power by the migrants/refugees/illegal immigrants. This turn of events produced two types of statelessness: a de facto kind under which refugees-turned-legal-citizens of India remained second-class citizens in their new nation-state, facing constant threats to their lives and livelihoods and without the same access to rights as their Assamese neighbors; and another group of descendants of Bengali migrants without access to citizenship at all, still formally stateless some seventy-four years after Partition brought them into the new state of India.

List of reading

Amalendu Guha, Planter Raj to Swaraj: Freedom Struggle and Electoral Politics in Assam, 1826-1947, New Delhi, People’s Publishing House, 1977.

Myron Weiner, Sons of the Soil: Migration and Ethnic Conflict in India, Delhi, Oxford University Press, 1988.

Monirul Hussain, The Assam Movement: Class, Ideology and Identity, New Delhi, Manak and Har-Anand, 1993.

Udayan Misra, The Periphery Strikes Back: Challenges to Nation-State in Assam and Nagaland, Shimla, Indian Institute of Advanced Studies, 2000.

Nandana Dutta, Questions of Identity in Assam: Location, Migration, Hybridity, New Delhi, Sage, 2012.

Priyam Goswami, The History of Assam: From Yandabo to Partition, 1826-1947, New Delhi, Orient BlackSwan, 2012.

Moushumi Dutta Pathak, You do not Belong Here: Partition Diaspora in the Brahmaputra Valley, Chennai, Notion Press, 2017.

Sajal Nag, Beleaguered Nation: The Making and Unmaking of the Assamese Nationality, New Delhi, Monahar, 2018.