January 24, 2022

Decolonizing Refugees: Exile and Political Possibility in 1960s Dar es Salaam

Among the figures haunting statelessness is that of the exile, the political refugee. Some of the best known stateless figures – in this and past eras – are those who became stateless or displaced through activism, forced to leave behind homelands and nationalities as a consequence of their political engagement. Exile, almost by definition, has always had a political charge – one that gained special traction in particular eras and moments. The 1960s was one of those periods, a decade that saw mostly leftwing political exiles take center stage in the dramas of decolonization, civil rights struggles, anti-war campaigns, and other protest movements sweeping across much of the world.

Within these movements and the imagination of the time, exile – and statelessness – came with a sense of political possibility. Although those who went into exile often did so under duress – anti-Apartheid campaigners, Black Power activists fleeing the FBI, young Africans from the continent’s colonial holdouts, Palestinian nationalists – their journeys were infused with visions of revolution and utopia. Going into exile meant seeking space to articulate visions of political change that were impossible to pursue on one’s home turf, where exploitation and injustice reigned. If the exile and the refugee – like statelessness itself – have traditionally been framed as marking a position of lack, here they bore a positive, sometimes even romantic, valence. They signaled political promise. This promise, embedded in the varied material conditions that structured political exile, also saw activists struggling to articulate political visions and demands that might transcend the horizon of the nation-state – or, at the very least, not be short-circuited by the latter’s dominance.

Going into exile meant seeking space to articulate visions of political change that were impossible to pursue on one’s home turf, where exploitation and injustice reigned. Here, the exile and the refugee signaled political promise.

Political exiles may have been fleeing a home, but they also joined and forged community; and “the Sixties” soon became synonymous with a signature set of sites of political activism: Berkeley, Birmingham, London, Paris, Prague. In the last few years, however, scholars and activists alike have begun slowly to take off their North Atlantic lenses and recall that some of the most vibrant, cosmopolitan of Sixties hubs were the capitals of newly independent African states that had just won striking victories against European empire. And Accra, Algiers, Cairo, and Dar es Salaam were not just critical sites for African decolonization. They drew political sojourners from across the world – especially those eager to shape political communities and projects that exceeded the bounds of their own nations and the nation-state form itself.

The Tanzanian capital of Dar es Salaam was one of the most magnetic of these sites. A simple list of just some of the more globally well-known of those who brought their work to the city provides a glimpse of its draw: Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, Angela Davis, Robert F. Williams, Amiri Baraka, Oliver Tambo, Eduardo Mondlane, Che Guevara, Ruth First, Walter Rodney, Immanuel Wallerstein and Giovanni Arrighi all spent time there during those years. As this roster suggests, the encounters Dar bred shaped movements far beyond the continent. Not just Southern African decolonization and pan-Africanism, but US civil rights, Black Power, and global Marxism were all shaped by Dar es Salaam in ways that have been forgotten but were well-known at the time.

Entrance to New Africa Hotel, Dar es Salaam, 1961. Image source: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

Visitors to Dar quickly noticed the buzz created by its international scene of political activists and operatives. A couple of examples of initial impressions by such sojourners help introduce features of this haven for exiles that make it a consequential vantage point from which to view the importance of statelessness to a range of Sixties movements. First, as the globe-trotting Polish journalist Ryszard Kapucinski famously described the atmosphere at one hotspot, the terrace of the New Africa Hotel:

All of Africa conspires here these days. Here gather the fugitives, refugees, and emigrants from various parts of the continent. One can spot sitting at one table Mondlane from Mozambique, Kaunda from Zambia, Mugabe from Rhodesia. At another – Karume from Zanzibar, Chisiza from Malawi, Nujoma from Namibia, etc…. In the evening, when it grows cooler and a refreshing breeze blows from the sea, the terrace fills with people discussing, planning courses of action, calculating their strengths and assessing their chances. It becomes a command center, a temporary captain’s bridge. We, the correspondents, come by here frequently, to pick up something. We already know all the leaders, we know who is worth sidling up to.1

Away from the commanding heights of the New Africa’s “captain’s bridge,” the scene was no less cosmopolitan, but was populated less by heads-of-state and movement leaders than by rank-and-file cadres whose status in Tanzania was juridically that of “refugees.” And for these refugees, housed in camps rather than in upscale hotels like the New Africa, or the Oyster Bay neighborhood of expatriates and officials, daily life in Dar had significant material challenges that it did not for movements’ leadership class. As John Gerhart, part of a group of Harvard students teaching at a school for political exiles, described it:

The refugees come looking for asylum, scholarships, political support, and finances for their operations. Help is usually forthcoming, though seldom the exact quantity or type desired. Most of the refugees are political exiles, forced to flee in order to escape banning orders or arrest. Many are students, who have come north looking for scholarships because higher education is denied them in their own countries. Others are school teachers, nurses, journalists, or musicians seeking an opportunity to follow their professions free from enforced discrimination and apartheid.2

But despite differences in the lives of leaders and cadres, the two groups nonetheless rubbed shoulders in Dar’s small-world geography of political exiles. And both also had in common the presence of expatriates of various sorts among them – fellow-travelers drawn to Dar by its increasing fame in left-wing circles around the world. As Prexy Nesbitt, a black activist from Chicago who would go on to prominence within the anti-apartheid movement, described his arrival in Dar on study-abroad from Antioch College:

[Ed and Gretchen Hawley] were already in Dar es Salaam and drove up to Nairobi, Kenya to meet me. Ed was working already then as the pastor to refugees in ’65 in Tanzania. And he had left our family’s church. And Ed was a great friend to our family, and we were a great friend to Ed. So Ed and Gretchen drive up to Nairobi and meet me, and we drive back from Nairobi to Dar in some old Peugeot. And immediately, the community that I become a part of is some of the ANC [African National Congress] refugees, who, a couple of them, are attending school at the University of Dar es Salaam. Through them I then meet the Harvard Tanganyika group. And through the Harvard Tanganyika group, and particularly though seeing a woman named Mary Yarwood, I would get introduced to the Mozambique Institute, to the AAI [African American Institute] school in Kurasini, and really get exposure to that whole community of Southern Africans living in Tanzania. So, I can remember, for example, going to speak to the African American Institute refugees about Malcolm X…. 3

Malcolm X pictured with students from the Harvard Tanganyika Project in Dar es Salaam, 1964 (photo taken by Maja Zimmermann, used with permission of Susan Carey and Ned Block).

These quotidian snapshots of life in this haven for exiles begin to hint at dynamics that make Dar es Salaam a useful vantage point from which to explore the importance of statelessness and exile to signature political movements of the 1960s, from decolonization to US civil rights. First, Dar’s scene was extremely cosmopolitan and global, in a way that included both the high-political and the minor-key: African heads-of-state, liberation movement recruits newly-joined, movement heavyweights like Malcolm, US college students from both elite and humble backgrounds, foreign correspondents from both sides of the Cold War, seasoned civil rights activists and African Americans for whom an African experience would lead to their involvement back home – all rubbed shoulders across an expatriate geography marked by a small set of embassies, hotel terraces, movement offices, training camps, and schools. As the quotations make clear, the cosmopolitan nature of this scene manifested at all levels of movement hierarchy, but (and here is the second point) it did so unequally. Not only were food, housing, education, travel, and funds all unevenly distributed, but so was access to expatriates – itself a potentially valuable resource, to which the rank-and-file were highly attuned. Where particular leaders were living, with whom they were seen, how close they were to expatriates, and how often they traveled abroad were keenly noted by cadres. These links to expatriates and the lifestyle markers that accompanied them would become objects of class struggle and political critique within anti-colonial movements themselves.

Frantz Fanon was among decolonization’s most powerful and globally influential voices, gaining an international audience with his searing 1961 work Les damnés de la terre (“The Wretched of the Earth”). The book was one of the earliest to see the moment of independence from colonial rule to be only one step in a struggle – and one that contained potential pitfalls for the masses.

One question predominated: would this struggle against colonial exploitation result in greater equality for all, or, as Frantz Fanon famously described it at the time, simply end with an African “bureaucratic bourgeoisie” replacing the colonizers at the top of a highly unequal nation-state whose borders and economic structure were rooted in colonial relations? Up and down the scale of class and racial privilege, the life of political exile produced attempts to avoid what many already sensed was a trap: the nation-state, which fragmented the African continent into dozens of colonially-derived territorial units, becoming an impediment to overcoming material inequality. However, as we will see, which of these visions would rise and which would fall depended highly on those very class divides that structured “comrade life” in exile.

The life of political exile produced attempts to avoid what many already sensed was a trap: the nation-state, which fragmented the African continent into dozens of colonially-derived territorial units, becoming an impediment to overcoming material inequality.

In terms of both ideology and practice, the political energies playing out around exile in Dar and the questions they generated carried significance far beyond Tanzania, Southern Africa, and the African continent as a whole. Because the city’s scene of exiled activists was so global in scope, the encounters there had a shaping power that radiated outwards along each of the networks the city knit together. Three exile networks were especially key in building Dar’s reputation as a hub for radical politics, and each brought unique perspectives to the city. First, this period saw Dar become Africa’s top destination for African Americans seeking political engagement with the continent. A diverse group, these migrants included Black Panthers fleeing FBI harassment, volunteers with a project to provide an African American alternative to the Peace Corps, “back to Africa” settlers, and hundreds of delegates to the 6th Pan-African Congress (6-PAC) held in Dar in 1974, a gathering organized around visions of the power that a politically united Black world might achieve. A second strand was composed of the Southern African liberation movements hosted there as a part of Tanzania’s commitment to aiding the battle against settler colonialism to its south. More than a half-dozen of the key anti-colonial organizations from South Africa, Mozambique, Angola, Southern Rhodesia, and South-West Africa had their headquarters in Dar in the 1960s and ‘70s, with a rotating cast of thousands of political refugees gathered around them. A third strand encompassed the sizeable contingent of fellow travelers drawn to work in Dar by its growing reputation in left-wing circles around the world. This was a diverse group – academics, teachers, journalists, aid workers, and lobbyists – attempting to leverage their professional skills behind the causes of anti-colonial nationalism, Tanzanian economic development, Marxist social-science, and Third World solidarity for which the city was known.

The Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO), founded in Dar es Salaam in 1962, was the main anti-colonial movement fighting for Mozambique’s independence. Upon independence, it assumed control of the state and has remained the ruling party until the present.

If each of these exile networks fed Dar’s politics in unique ways, each was also shaped by the others. For instance, if one tracks the people for whom Dar became a temporary base, we see US civil rights and Southern African liberation movements influencing one another in a feedback loop that showcases the importance of exile for each. The story of Eduardo Mondlane, the President of Mozambican anti-colonial movement FRELIMO, is a revealing example. The son of a chief, Mondlane sought higher education in the U.S. to circumvent the notoriously limited opportunities for Africans within Portuguese-colonized Mozambique. A devoted Christian, Mondlane arrived at Oberlin College in 1951 and began attending the local Congregationalist church, which was led by a young pastor named Ed Hawley who was involved in efforts to aid local desegregation campaigns. Hawley was impressed with Mondlane’s Christianity-infused hope for a free Africa and set Mondlane up with speaking engagements at church- and student-based retreats all over the Midwest. At one of these church retreats, in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, Mondlane met Janet Rae Johnson, a 17-year-old white American from one of Chicago’s wealthy suburbs who was captivated by Mondlane’s talk and began a correspondence with him that soon turned romantic. Five years later, the two would marry in a ceremony presided by none other than Ed Hawley, who was now pastor of a social-justice oriented church in Chicago.

Funeral of Eduardo Mondlane in Dar es Salaam, following his assassination in February 1969. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Many of these connections Mondlane developed while abroad had generative capacity that extended beyond America’s borders. As we saw with Prexy Nesbitt’s recollections above, Hawley – who would years later describe himself as one of the “thousands of Americans, black and white, who first became aware of the aspirations to independence of colonial Africa through the speeches of Eduardo Mondlane” – would join Mondlane in Dar in the 1960s to work with political refugees from Southern Africa; his wife, Gretchen, would teach at the Mozambique Institute, the FRELIMO school there. 4 Janet Mondlane herself would become a central figure in FRELIMO as the director of the Mozambique Institute once she and Eduardo moved to Dar. And if connections like these from Mondlane’s time in the US would end up following him to Dar, as we saw with Nesbitt, these trails sometimes reproduced themselves across generational lines, leading younger activists to Dar as an entry-point to further political engagement both at home and with Africa.

Politically-engaged students were not the only ones taking notice of Africa’s prominence on campus. The telling fact that Project Tanganyika would be pulled into the CIA’s effort to direct funding toward a panoply of private groups like the African American Institute (a prominent black-run organization that helped fund the HTP and Kurasini) did not prevent the connections that it generated from exceeding the visions of US officialdom.

Nor were the mutually enriching connections between African American civil rights and Southern African liberation that Dar es Salaam bundled together limited to prominent figures like Eduardo Mondlane. In the case of the Harvard Tanganyika Project (mentioned in both Gerhart’s and Nesbitt’s recollections), a volunteer-abroad program birthed by student initiative at Harvard to aid newly-decolonizing nations in Africa would, however improbably, thrust groups of mostly white American undergraduates into the very center of Dar’s world of political exiles. In the early 1960s, Africa was a more important part of the US campus zeitgeist than we tend to remember – a prominence that, until the end of the century at least, canonical histories of civil rights and the New Left would often efface. When the HTP began in 1961 (preceding Kennedy’s Peace Corps), politically engaged students enthusiastically signed up for it as a way to get out of Cambridge and onto the frontlines of global change. Within a year, Tanzanian officials and leaders of Dar’s Southern African liberation movements had seized upon the Project as a way to establish a school for young political refugees leaving the still-colonized regions of Southern Africa to join the political struggle in exile. For these rank-and-file cadres, this school – called Kurasini – provided a social hub, and the Harvard students teaching there mirrored, if only dimly, the expatriate connections that cadres saw their leaders enjoying at a higher level on the embassy circuit. For the Harvard students, the Project was also, perhaps even more, consequential. For many it would prove to be a formative pivot-point: it inspired a remarkable number of them to join the anti-segregationist protest movement in the American South Freedom Summer upon their return to the U.S.

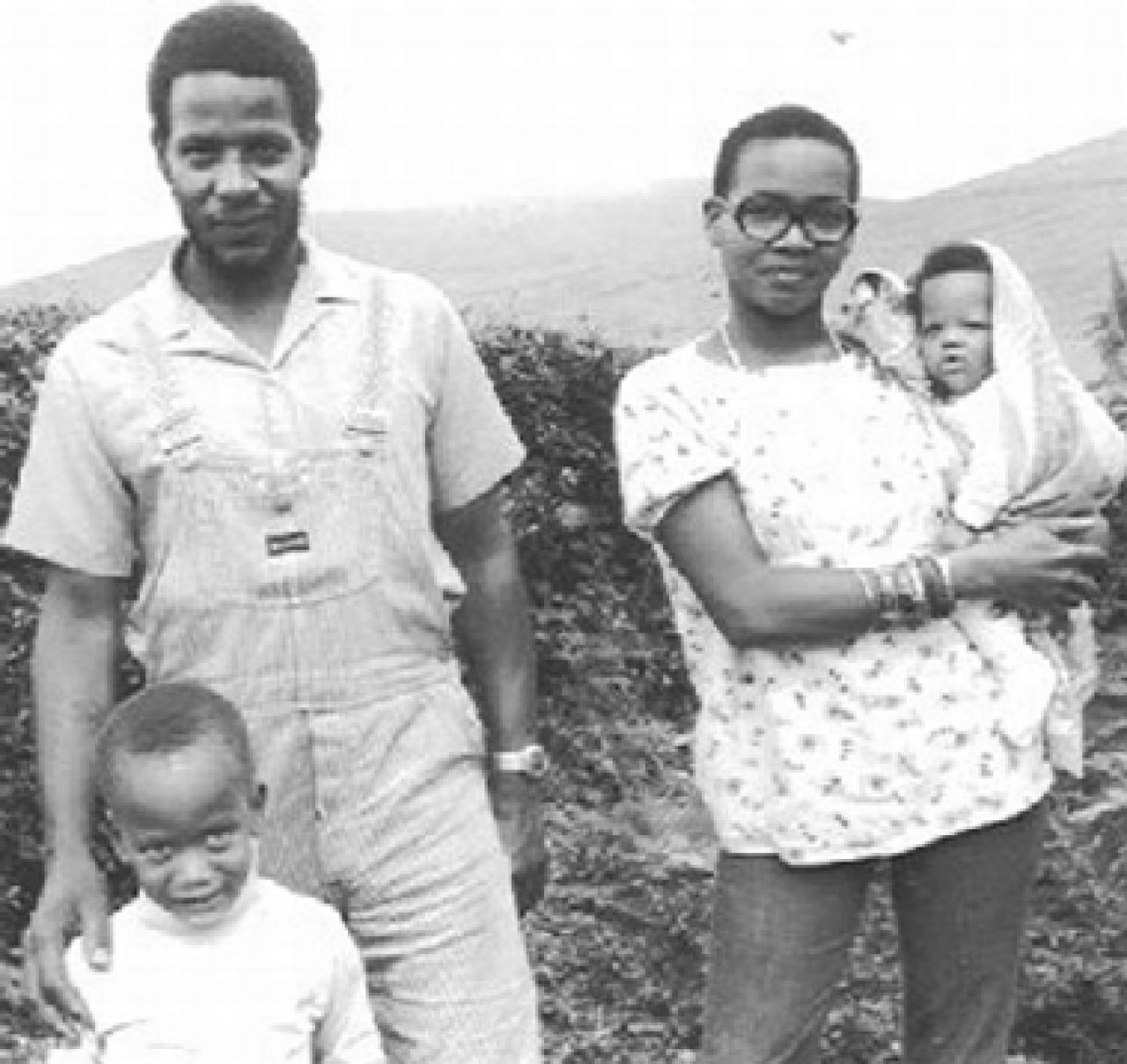

Pete and Charlotte O’Neal with their children in Arusha, Tanzania, in the early 1970s. Source: UAACC

For African Americans, Dar es Salaam became an even more important beacon. Accra, Ghana had been the first of such havens for those seeking to go into exile in Africa (including W.E.B. DuBois and Paul Robeson). But after Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah was overthrown in a 1966 coup d’état, Dar quickly replaced Accra as the continent’s number one destination for Black Americans seeking engagement with Africa. For many African Americans in Dar, their time there sparked an expansion in political sensibilities through connections with the city’s Southern African liberation movements – connections that fed into later lives in anti-apartheid activism. For others, relations with the Tanzanian government challenged assumptions of racial solidarity and prompted tensions fueled by divergent political goals. The 6th Pan-Africanist Congress, held in Dar in 1974, unexpectedly became a watershed in the struggle between cultural nationalism and Marxism within US black politics. The influence of Southern African liberation movements played a critical but largely forgotten role in this intellectual history. With all of these experiences, the solidarities and discontents that attended African American activists in Dar grew out of, and then fed back into, the landscape of U.S. black politics.

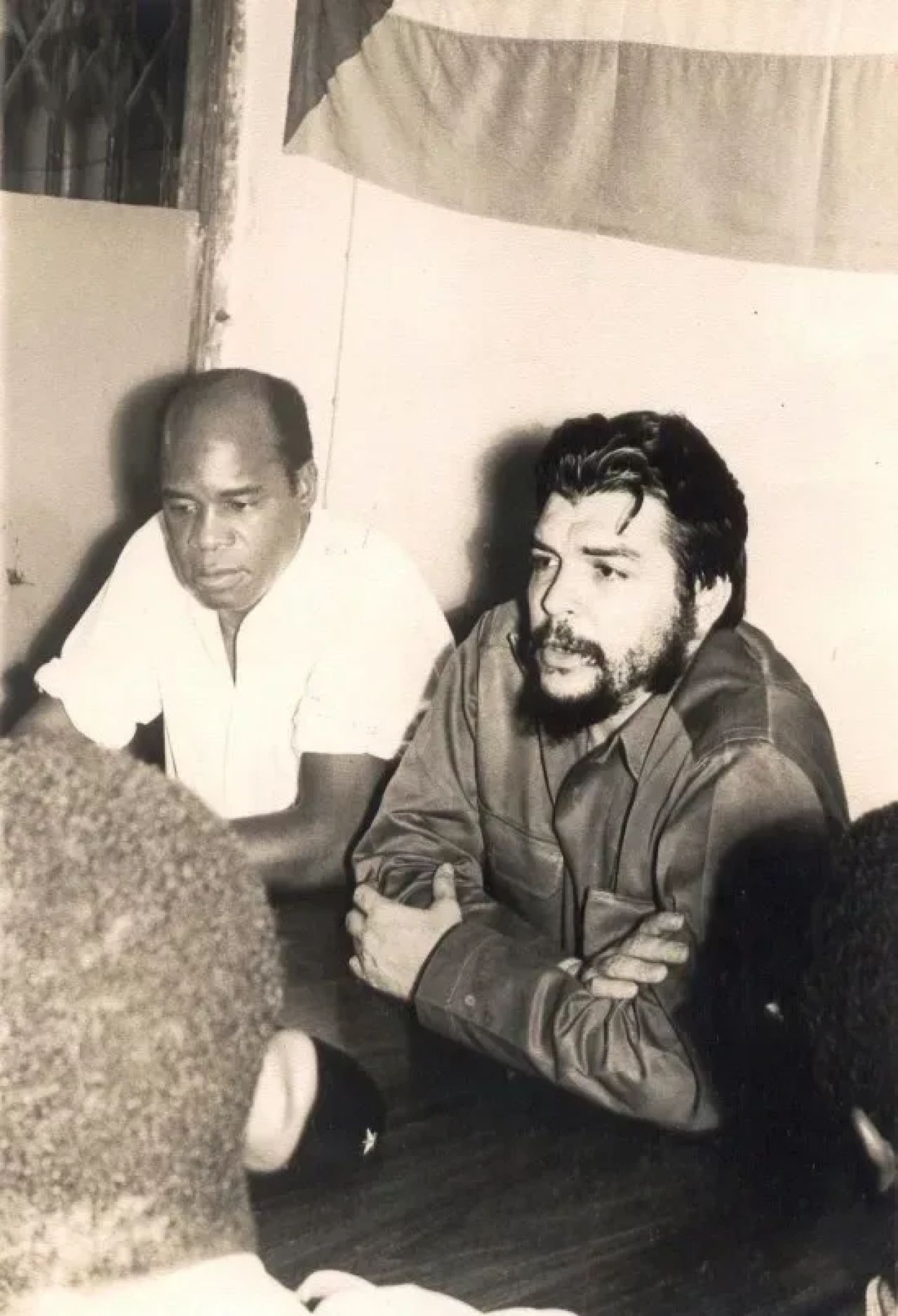

Che Guevara, pictured with Eduardo Mondlane, addressing liberation movement leaders in Dar es Salaam, February 1965. Source: AAPRP

With global Marxism as a significant part of Dar’s exile scene, we see it too shaping and shaped by the city in a multi-directional fashion. Most accounts of Tanzania’s relationship to Marxism begin and end with ujamaa, President Nyerere’s attempt to craft a Maoist-adjacent African socialism. As important as ujamaa was, particularly for grappling with rural life in a largely non-industrialized country, Dar es Salaam also played host to a number of other revolutionary projects, most of which thrived on the city’s exile scene. Taking note of these can both help build a more global view of Marxism’s 20th-century itineraries and underline the importance of exile to this history. The Marxist projects running through Dar touched both practice and theory. Che Guevara, perhaps the foremost practitioners of a Marxist model of transnational insurgency, used Dar es Salaam as a rear-base for his 1965 mission to aid Congolese rebels battling Joseph Mobutu’s US-aligned regime in the wake of Patrice Lumumba’s assassination. Although Dar was not the geographically closest capital to the rebel base in Congo’s east, its infrastructure of support for revolutionary exile projects was unparalleled in the region, and made it an attractive site from which to work. Even if Che’s relatively thin grasp of the way class politics structured comrade life in Dar produced tensions with movement leaders, his time there (memorialized in his Congo Diaries) was still important for widening the horizon of possibility for transnational left politics in a manner not subsumable to the nation-state.

On the theoretical front, the University of Dar es Salaam throughout the 1960s and early 1970s was a major destination for leftwing academics. They spanned a range – from those, like Terrance Ranger, who had been expelled from Southern Rhodesia for consorting with African nationalists, to world-systems theorists like Giovanni Arrighi, Walter Rodney, and Immanuel Wallerstein, to high profile visitors like C.L.R. James – all drawn to the UDSM by its growing reputation as a fount of Marxist scholarship. Nor was the University simply on the receiving end of academics whose careers were already established: indeed, many of those listed above would write their signature works from Dar, such as Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, an iconic text composed amidst the atmosphere of intense intellectual debate at the UDSM. Students were a major part of this richness, in ways that went beyond sitting at the feet of their faculty mentors. A group called USARF (University Students’ African Revolutionary Front) was founded by a diverse cohort of Marxist students from around East Africa; their activities ranged from publishing a journal that was later shut down by the government to forming a study group with expatriate faculty like Rodney to bringing speakers like C.L.R. James to campus. Although they were allied with the radical faculty, these students were also much more intensely focused on pushing Nyerere’s government, which they regarded at risk of turning into a “bureaucratic bourgeoisie,” further to the left.

Walter Rodney addressing a crowd in Dar es Salaam in the 1970s.

If UDSM’s expatriate faculty would achieve significant fame for shaping a global conversation around how countries “underdeveloped” by imperialism could survive a capitalist economy arrayed against them, the international group of Marxist students on campus would prove a more lasting and potent force locally. Herein lies one iteration of an irony that troubles the relationship between the material life of Dar’s exile communities, one the one hand, to statelessness as a sometime feature of the political visions that these communities produced, on the other. In the case of the UDSM, when we consider the ideas generated by the two groups, expatriate faculty and African students, it was in the faculty’s writing that would help constitute “dependency theory” or “world-systems theory” where we see a sustained attempt to explicitly critique the nation-state as an inherently unsatisfactory form for material justice.

Rodney, Arrighi, and Wallerstein all saw the dominance of the nation-state as an obstacle to material well-being in the ex-colonial world, a political form that kept capital’s profits secure by fragmenting attempts to “de-link” from a global capitalist system. Divided into nation-states along colonial boundaries, the result was a Third World trapped in a dependence on the industrialized north: producing raw materials in exchange for finished goods, with little way of industrializing or becoming self-sufficient. Dar’s Marxist students in USARF, while generally in agreement with their faculty mentors’ analysis of the global system, tended to be much more focused on what they saw as a more immediate and pressing concern: pushing their own national government further to the left on issues such as nationalization and re-distribution of capital and property. If the contributions of UDSM’s expatriate faculty to dependency and world-systems theory would go on to achieve significant visibility within global Marxism, UDSM’s radical students were arguably more intimately attuned to the material stakes of life in the postcolony.

Dar’s Marxist students in USARF, while generally in agreement with their faculty mentors’ critical analysis of the global system, tended to be much more focused on what they saw as a more immediate and pressing concern: pushing their own national government further to the left on issues such as nationalization and re-distribution of capital and property.

The relationship between statelessness as a material condition of life, on the one hand, and visions of political futures that transcended the nation-state, on the other, becomes even more complex as we begin to scale down through the class hierarchies of Dar’s exile scene. For “comrade life” in exile hubs like Dar were also spaces structured by tiers and hierarchies, and the effects of these encounters would vary for different groups of actors. For some, as we have seen, exile worked well as a platform for new connections and political growth. This could be said for movement leaders like Mondlane, Harvard Tanganyika Project volunteers, African American activists, and Marxist faculty at the UDSM. For these constituencies, the sheer capaciousness of the connections encouraged by Dar’s small-world exile ecology allowed for an extension of political horizons, fueled commitments to transcending the nation-state, and were sometimes parlayed into lifetime careers in politics. We have already seen an example of this with dependency theorists at UDSM; but in a less Marxist vein, not a few nationalist leaders became interested in dreams of uniting multiple independent nations into federations. Often inspired by pan-Africanists such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, such plans (for an East African Federation, for instance) were powerful dreams, even if they remained largely on paper. For many African American sojourners and those involved in the HTP, their time in Dar prompted involvement in civil rights activism back home – now infused with Third Worldist, anti-colonial sensibilities that would peak with groups like the Black Panthers.

But there were some – less mobile, less elite, more exclusively African – for whom exile worked in other ways: still generative, but differently so. This was the case for the thousands of young cadres who, like their leaders, had come to Dar es Salaam to build political lives in a movement hub, but for whom the city was a slightly different kind of space. Classed as “refugees” by the Tanzanian government, these rank-and-file activists were housed in camps like Mgulani, unlike their leaders in Oyster Bay, without the privileges of travel, high-end lifestyles, and access to government officials, and dependent on a small allowance. But since the world of exiles was such a small one, they still circulated in the same small-world circuit as their leaders and rubbed shoulders with them – embassies, parties, party congresses, etc, were all points of contact. And they were served by expatriate volunteers from the West – political itinerants themselves, but of a different sort, neither refugee nor diplomat. The overlapping character of these circles meant that movement rank-and-file were witness to, but excluded from, their leaders’ lifestyles. Consequently, privilege and consumption became a critical point of contention. As one group of rank-and-file dissidents put it in a Swahili language manifesto, they condemned those leaders “who just like eating money and making a nice life for themselves there in Dar es Salaam, and marrying white wives and drinking beer and whiskey and buying big houses over there in Oyster Bay…and leaving their compatriots to die of hunger while they get money from foreign countries….”5

Privilege and consumption among the exiles became a critical point of contention. As one group of rank-and-file dissidents put it in a Swahili language manifesto, they condemned those leaders “who just like eating money and making a nice life for themselves there in Dar es Salaam, and marrying white wives and drinking beer and whiskey and buying big houses over there in Oyster Bay…and leaving their compatriots to die of hunger while they get money from foreign countries….”

At the level of the rank-and-file, some of the same associations that accompanied an exile scene filled with a jet set of expatriate revolutionaries fueled a persistent Fanonist critique aimed at inequality and unshared privilege within such movements. Here, the battle for liberation from colonial exploitation was not simply about independence for a national territory, but about the distribution of resources: who would benefit from independence once achieved? Could leaders be relied upon to distribute these resources equally? Such questions formed a vision of decolonization as an expansive liberation: not just putting a colonial state in new hands, but a revolution to liberate all from the inequalities that were in-built to the colonial system. And this vision remained a persistent tradition of political critique after independence, with a power to put elites on notice, even if it rarely won out.

The economic and world-systems thinker Samir Amin has defined this concept of de-linking as “a necessary ‘break’ from this world capitalist system… that is to say, the refusal to submit national-development strategy to the imperatives of ‘globalization’ “ - in "A Note on the Concept of Delinking".

The nation-state, too, proved a formidable impediment to the realization of other models or foci for political demands after empire. For a certain class of nationalist elites it was like a siren call, and federation designs tended to succumb to the inertia of (neo-)colonial territoriality and the advantages in taking over an extant state structure with which international capital already had dealings. For the rank-and-file of these movements, political visions remained focused on a non-state-based (or at least state-agnostic) politics of material equality; but often the state was deployed to quash rather than realize them. Dependency theory may have had the longest lasting power, but here too the impact was greatest in theory: countries that did try to implement “de-linking” tended to have these efforts fall victim to a powerful set of laws designed by the wealthy West and international institutions. These legal structures “encased” capital in smooth corridors of mobility, while exerting pressure upon increasingly indebted Third World states to sign on to “Structural Adjustment” bailouts that imposed austerity and further lowered barriers to foreign investment.

Countering notions of a “free market,” Quinn Slobodian argues in The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism that neo-liberal capitalism was deliberately structured to “encase” capital in paths designed to protect profits.

If the conditions of exile in a hub like Dar fed both global solidarities among activists of different stripes and critiques of inequalities within movements by less mobile comrades, each of these dynamics helped mold Sixties political forms, their victories and losses. The rich interactions incubated in Dar between African American civil rights and Southern African liberation, for instance, sharpened each movements’ self-analysis, deepened their purchase, and broadened their scope. It would be hard to separate these influences from the victories of desegregation and decolonization that these movements won. At the same time, Dar’s exilic cosmopolitanism resonated differently for the non-elite of the city’s politically engaged young. For those down-scale in terms of rank – the lumpen cadres of FRELIMO or even, perhaps, the students of USARF (relative to UDSM’s expatriate faculty) – their relative immobility amidst the globe-trotting culture of exile prompted a different kind of political critique: a commitment to ensuring that questions of material inequality, redistribution, and the stewardship of resources were kept in the foreground. These latter demands – and the rank-and-file constituency that made them – were no more trusting of the nation-state system than the explicitly transnational frames of the more mobile exiles. They did in the end, however, tend to be subsumed much more completely within the nation-state form. This outcome might be seen as particularly tragic, given that it was these less-privileged, less-mobile members of Dar’s community of exiles that had most at stake materially in national independence not becoming simply a national “bureaucratic bourgeoisie” replacing its colonial predecessors.

For those down-scale in terms of rank, their relative immobility amidst the globe-trotting culture of exile prompted a different kind of political critique: a commitment to ensuring that questions of material inequality, redistribution, and the stewardship of resources were kept in the foreground.

In recent conversations on the Left, the signature movements of the 1960s have begun to be freighted with an interesting ambivalence. On the one hand, they are hailed for mobilizing tremendous numbers of people that enabled crucial victories on fronts of decolonization, racial and gender equality, and more. On the other, the years of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s represent an economic pivot-point ushering in a harsher form of neo-liberal capitalism, with some commentators suggesting that the socio-economic demands of the era’s protest movements (even those generally regarded as victorious) went unmet.

This is an ambivalence that a vantage point like Dar es Salaam, outside the “global North” and its Cold War blocks of East and West, can help us see afresh. Not only does the city make clear the oft-overlooked importance of both Africa and exile – that key cognate of statelessness – to some of the Sixties’ classic movements. Even more challenging, it offers an example-in-miniature of how these movements’ mixed legacies – their victories (fueled by kinds of connections made by Dar’s mobile exiles) and defeats (like those of Dar’s less-mobile “left behinds”) – emerged in relation and close proximity to one another. Both help illuminate how the phenomenon of leaving one’s country, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, to pursue politics from exile was key to the praxis of transnational solidarity in the 1960s. And, in a more tragic register, it also shows how those who had most to lose under the enshrinement of the nation-state as a hegemonic political form were precisely those for whom transnational alternatives remained most out-of-reach.

List of reading

Che Guevara, Congo Diary: Episodes of the Revolutionary War in the Congo (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2021).

Karim Hirji (ed.), Cheche: Reminiscences of a Radical Magazine (Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota Press, 2010).

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, 60th Anniversary Edition (New York: Grove Atlantic Press, 2021)

Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (London: Verso Press, 2018)

Seth Markle, A Motorcycle on Hell’s Run: Tanzania, Black Power, and the Uncertain Future of Pan-Africanism (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2017)

Footnotes

- Ryszard Kapuscinski, The Shadow of the Sun (Vintage, 2001). back

- John D. Gerhart, “Dar es Salaam Becomes Center of Refugee Intrigue; Nine Exiled Regimes Have Headquarters in the City,” Havard Crimson, 25 September, 1964. back

- Aluka archive, “No Easy Victories” collection, Prexy Nesbitt, interviewed by William Minter, Chicago, 31 October, 1998. back

- Edward A. Hawley, “Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane (1920-1969): A Personal Memoir,” Africa Today 26.1 (1979): 22. back

- Mozambique African National Union, “Habari ya MANU Chama cha Upinduzi wa Mozambique” (Nov. 5th, 1965), p. 2. USC digital collection, “Emerging Nationalism in Portuguese Africa.” back